- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

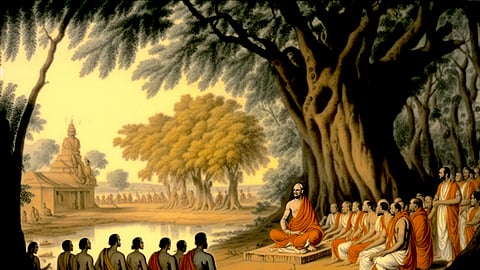

LET’S BEGIN BY CONSIDERING the simplest definition of education in the Sanatana tradition: sā vidyā yā vimuktaye. Meaning, that is education which liberates us. Which evokes the question: liberates us from what? The answer to this question is on two planes. On the plane of our “real” or daily life, real education is that which endows us with the inner strength and arsenal to fight and overcome losses, troubles, dejection, pain and suffering of various kinds that we all have experienced at some point or the other in our own lives. On the philosophical plane, it indicates Moksha, Mukti, etc. It is said that a profound sense of dejection awakens a profound yearning for philosophical truths.

In the context of this essay, one of the central goals of our ancient ideal of education was to create a Praja, or a citizen in the truest sense of the word. Everything else came second. Notwithstanding what a person became later in life – a minister, bureaucrat, businessmen, professional, sports star – his standing, status and respect in society derived primarily from being a good citizen. Today, we have the exact inversion of this ideal: respect has been detached from ethics and conduct. All that we have is an illusion of respect wearing the patina of power and vulgar wealth.

Overall, the Hindu ideal and practice of education was designed to inculcate a sense of moderation and contentment in our external life by emphasising the cultivation of certain fundamental values in our inner life. This lends stability to the external life and perpetuity to this profound value system. The brilliant scholar, Prof M. Hiriyanna captured the whole essence of the Sanatana educational ideal in these words: “the aim of education is not to inform the mind but to form it.” Or to quote the prolific Ananda Coomaraswamy, “From the earliest times, Indians have thought of the learned man, not as one who has read much, but as one who has been profoundly taught.”

Some of these values include a voluntary obedience to Rta (the Cosmic Order), Satya (Truth), Dharma. Here, “voluntary obedience,” means obedience to the unenforceable.

We can neither physically see nor grasp Rta, Satya and Dharma, yet in obeying them, we derive an immense benefit both as individuals and as members of a community and society. On another level, this honorary obedience automatically reduces the need for newer criminal or civil laws and punishments. When we think about it, any country or society which has an excessive number of laws only means that its population needs to be constantly kept in fear. Our ancient sages had solved this problem by emphasising on the primacy of Dharma over Danda (punishment).

Values like Rta, Satya and Dharma were not merely theories or empty intellectual constructs. For countless centuries, these values were lived in the practical life of the Hindu society in several ways. For example, through the performance of Yajnas (a national system of sharing resources for the collective good), Daana (the voluntary submission of a part of our wealth, resources or labour for the larger social and national benefit), and Tapas (setting aside time for personal contemplation leading to inner refinement). These values have truly stood the test of time and are the true pillars of the Sanatana civilization.

We can verify the longevity of this value system truth even today. For example, it is still common to see all kinds of third-rated politicians and street goons proudly boasting about how they have been doing Annadaana and mass marriages (Kanyadaana) for say, 10 or 20 years, and therefore, “vote for me.” In another realm, these persons are criminals fit to remain in prison. However, they subconsciously, somehow, they know that conducting Annadanam, Kanyadanam etc., are virtuous acts that bestows respect that they don’t and can’t command.

All of this fundamentally indicates the continuance of these Sanatana civilizational and cultural values.

To put this in another fashion, the ancient Hindu ideal and practical system of education emphasized on the living aspects of these values and not merely abstract theories. Thus, education in India fostered and preserved society and culture by emphasizing on the continuous moral and spiritual refinement of the individual. In turn, the society and culture nurtured this educational system.

But to fully understand the genius of our educational heritage, it is essential to understand Sanatana Dharma itself. One cannot look at our education or society or culture or customs in isolation. Everything is intimately connected with invisible links that make this an organic whole in a beautiful manner. Like countless threads that make up a gorgeous dress.

In our educational system, there was no separation between “Dharmic” and “education.” If you lost one, you lost the whole thing. This is pretty much what has occurred in recent times as we shall see. In this case, Dharma also meant the wholistic application of this integrated education in all spheres of our life, throughout life.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.