- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

There is a whole school of American Jewish writers who spend their time damning their fathers, hating their mothers, wringing their hands and wondering why they were born. This isn't art or literature. It's psychiatry. These writers are professional apologists. Every year you find one of their works on the best-seller list. Their work is obnoxious and makes me sick to my stomach. I wrote Exodus because I was just sick of apologizing—or feeling that it was necessary to apologize.

Leon Uris

Sixty-three years later, Leon Uris’s sledgehammering words of defiant courage in the face of pervasive pusillanimity stand both as a beacon of light and as an eternal reminder that truth has few friends. His classic Exodus is still relevant not only because of Uris’ abiding conviction in Israel and the Jewish cause but because it is a near-contemporary showcase of that other truth: that literature (or generally speaking, art) is an extraordinarily powerful—and in many cases, an unerring key to understand history, civilization, and culture in the profoundest sense: through real people.

We find a deeply philosophical expository echo of the truth of Leon Uris’ words in the preface of Dr. S.L. Bhyrappa’s explosive bestselling literary phenomenon, Aavarana. On another occasion, responding to a question on whether he didn’t feel scared to write such a no-holds-barred novel, Dr. Bhyrappa said, “my view of literature is that it is a quest for truth, and if I don’t tell it even now, I think that there will be no meaning for my life. The freedom of expression that our Constitution guarantees us also includes the freedom to tell the truth.” [Paraphrased]

This in my view, is one of the simplest formulas for the conquest of fear.

On the level of pure passion, the angry lament of Leon Uris applies a hundred percent to post-Independence Indian “literature,” about the partition of Bharatavarsha, one of humankind’s greatest tragedies engineered by the combined forces of two Abrahamisms. Literary works based on the Partition are exactly that: an agglomeration of textual apologia, an attempt to induce civilizational amnesia in the present tense.

A brief contrast of the global impact of Exodus will brilliantly illustrate the existential grand canyon of post-Independence literary shame in India. Here are a few quotes:

Two months after the tenth anniversary, a novel was published in America that changed the public perception of Israel and the Jews. Exodus by the Jewish US ex-marine Leon Uris became an international publishing phenomenon, the biggest best seller in the United States since Gone with the Wind. Both the novel and the subsequent movie thrust Israel into the lives of millions, and with it initiated a new sympathy for the young country.

Jill Hamilton: God, Guns and Israel

[Exodus is] an antidote to the public silence of American Jews… Something fundamental changed among American Jews as a result of the book.

Mathew Silver

[The effect of Exodus] is so extraordinary that I wanted to go and fight for Israel, even die, if need be, for Israel. Israel spoke to the need I had as a young black man for a place where I could be free of being an object of hatred. I did not wish I were Jewish, but was glad that Jews had a land of their own...

Julius Lester

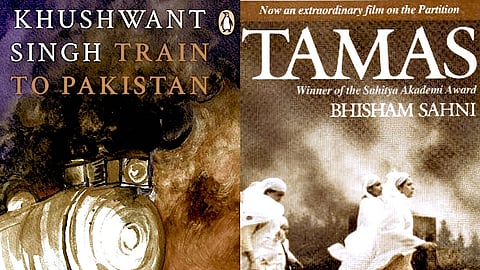

Which literary work immediately strikes your memory when Partition is mentioned? Until recently, it was the Nehru-cupbearer, Khushwant Singh’s eminent apologia titled Train to Pakistan. This shameless pamphlet, disguised as literature, stood unchallenged for decades as the unquestionable Koran of the Nehruvian literary establishment. Then there is Qurratulain Hyder’s voluminous Urdu novel, Aag ka Dariya (River of Fire), ambitious in scope but expectedly secular in its outcome. The fact that she chooses the fall of the Nanda dynasty to begin her epic mound of nonsense is quite telling. Next, we have the traitor Yashpal’s Hindi novel, Jhoota Sach (False Truth), which is a Comrade’s telling of the Partition through the tainted spectacles of class warfare. Enough said. Of course, the less said about Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas, the better. But the undoubted granddaddy of all Partition “literature” emerging from India is Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, which does contain some flashes of honesty but as a whole, the work is clearly tailored to the former colonial master’s sensibilities. The Booker Prize is the best proof of this.

The near-unanimous “conclusion” of all these works is this: no one person or one community is to blame for the Partition. It appears that all of humanity in India decided to voluntarily plunge into murderous insanity. In purely aesthetic terms, a work of literature should not have a conclusion because life itself is a continuum, not a conclusion.

This sort of “literature,” as Uris said, makes us sick, it makes us hate our father and mother, it makes us ashamed of and incites us to disown our own heritage. It distorts and depresses because it prevaricates. But lest I be accused of partiality or bias, here’s a handy test to determine the true mettle of creative literature on the Partition that appeared after “independence” - check the awards the authors received and check the general tenor of reviews.

While I am no fan of prescriptive literature, it must be said that when the author chooses a contemporary theme, honesty, and not audience, must drive it. Creative liberty is not an excuse for lying. Interpretation cannot become a Persian carpet to hide evasiveness.

As a historical event, the Partition was the savage triumph of a virulent Abrahamic fanaticism which had lost its imperial power but never stopped its ugly quest for reclaiming that power which is needed to sustain this fanaticism. It reclaimed it partially in the form of Pakistan, a usurped geography named after a religion, and after reclaiming it, set about permanently erasing the historical markers of this geography. For a fairly detailed explanation of how this works in real life, how it impacts and scars and mars and brutalizes, see The Dharma Dispatch series on the forgotten Hindu geography of Pakistan.

As a theme for a profound literary exploration of the Partition, the story should actually begin from the alien Islamic invasions of India, and not the clever-by-half deception of Aag ka Dariya which begins with the downfall of the Nanda dynasty. Or, if the author is untalented or lacks this sort of sweeping erudition, it can begin with the death of Aurangzeb because the modern roots of the Partition, most visibly, were planted in that period. One branch of that poisonous tree that grew up is now Pakistan. And now, over the last decade, we notice other trunks on our TV “debates” where assorted Mullahs and Imams unapologetically say that Mahmud of Ghazni and Aurangzeb are the true heroes of Islam in India.

In many ways, seventy-five years after the Partition of India provides a fertile ground for not only a dispassionate literary exploration of the tragedy, but a virgin field for truth-tellers, especially those who are genuinely disgusted with such phony passages masquerading as profound literature:

The Indo-Muslim life-style is made up of the Persian-Turki-Mughal and regional Rajput Hindu cultures. So, what is this Indianness which the Muslim League has started questioning? Could there be an alternate India?

Aag ka Darya

In the Sanatana tradition, poets and litterateurs are seated on the same high pedestal as the Rishis. The Partition is both an overwhelming invitation to and a far-reaching challenge for present-day creative writers to test for themselves how best they can elevate themselves to this high pedestal.

Dr. S.L. Bhyrappa pioneered the path with Aavarana. If a tenth of that summit is reached, that is saying a lot given the present aridity in the field of creative fiction.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.