- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

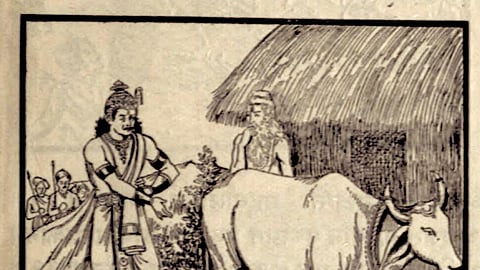

THE STORY OF THE RISHIS VASISTHA AND VISVAMITRA is unarguably one of the more lofty summits of our cultural and literary heritage. Occurring first in the Rg Veda, it is as ancient and as exalted as our spiritual civilisation. “Ancient” in the sense of “perennial.” The incredible transformations that this story has undergone from that civilisational dawn up to the flowering period of the Puranic Era merits a separate chapter.

The Fifth Mandala of the Rg Veda is composed by the Visvamitra Family. Also, in the Third Mandala, several verses are dedicated to cursing Vasistha and his family in rather harsh terms. This is the selfsame Rg Veda that accords the most illustrious pedestal to Vasistha, the Noblest of all Rishis. It equally celebrates Visvamitra as the courageous sage who rescued Sudasa and adopted Sunashepa as his own son. Above all, Visvamitra was the Draṣṭāra (visionary) who had realised the Gayatri Mantra.

But by the time of the Ramayana, the well-known story had undergone a profound transformation. Maharshi Valmiki tempered the sagely enmity by setting in the backdrop of an extraordinary confrontation which culminates in Visvamitra elevating himself to the status of a Rajarshi. The story of the process of his elevation has illustrated and expounded upon the fundamental values that make up the Sanatana civilisation.

Needless, Visvamitra occurs in a profuse fashion in the Mahabharata as well: for example, in the Adi, Vana, Salya, Drona, Shanti, Anushasana and Mausala Parvas.

And by the time of the Puranas, Visvamitra’s story acquired substantial wings. For example, the Devi Bhagavata gives us the celebrated story of Harishchandra, who went on to become one of the greatest cultural idioms of Bharatavarsha. Harishchandra is still the epitome of and a synonym for truth in the Hindu psyche.

In the non-Puranic annals, we notice Visvamitra in the second Taranga of Kathamukhalambaka in the Kathasaritsagara, in which he curses a celestial danseuse named Vidyutprabha for trying to seduce him.

However, the most enduring seed-bed of the story fleshing out the hostility between Vasistha and Visvamitra is their encounter in the Ramayana. Both the specifics and the aftermath of the encounter have left their lasting imprint on our cultural and literary heritage.

DEVUDU NARASIMHA SASTRY, one of the most acclaimed litterateurs of Kannada who blazed an independent path in the last century, gives us an evocative, brilliant and insightful depiction of this encounter in his pathbreaking classic, Mahabrahmana. The work easily ranks as one of the classics of world literature and continues to run into multiple reprints. The genius of Devudu is his original brand of amalgamation of the various versions of this celebrated Vasistha-Visvamitra story and then owning it: to the extent that after reading Mahabrahmana, it is hard to visualise it in any other manner. As a Vedic scholar who had mastered Sastric learning in the traditional mould, there was no way Devudu could portray either Rishi in a less-than reverential light. But because the hostility was real and its story was spread over so many copious annals, he summoned his creative Sarasvati to sublimate it. What we get is an inimitable masterpiece that could emanate only from a Rishi.

But before we can examine Devudu’s portrayal of the pivotal Vasistha-Visvamitra confrontation, an essential literary backdrop drawn directly from this Rishi’s own words, throws a floodlight of guidance. The following is a translated excerpt taken from Devudu’s All India Radio lecture dated January 16, 1960, two years before he attained Sadgati.

”In my view, literature is the expansion that occurs in all aspects of our life. To phrase it in the words of our ancients, literature is the happy penance undertaken in pursuit of the four Purusharthas. It is the device of devoting oneself to Paramartha even while leading life in the material world. However, the question arises: “does contemporary Kannada literature have this quality?” The answer: our Dharmasastra extols even an infertile cow as the Kamadhenu. The quality will develop eventually, there is no hurry. But for this to occur, people who have taken up creative literature must first introspect within.

“Contemporary Indian literature is an imitation of the West. Literature in the West developed through unceasing conflict. There, if a writer chose one path, another writer would ask, “why shouldn’t I choose the opposite or a different path?” Thus, the path that was trodden by hundreds of such folks lost the capacity to produce grass. This barrenness was given various names such as “highways” of Western literature. However, the motivation that comes from this state of affairs is not faulty by itself. But the blind imitation that it has birthed in our own literature is unarguably wrong.

“In its source-fount, the purpose of our literature must exude joy. Our contemporary litterateurs claim that they will rectify society through their literature. Sure, nobody says no. But my question: has what we have written first rectified ourselves? Besides, there is a new formula among our writers: of earning renown through exposing the defects of others. Apply this formula to music and see what happens. There, if we need to clearly define a Taala, we must first list out everything that it is not. Is this even practically possible? Even if it is, what is the ultimate point of such an exercise in negation?

“Fundamentally, the nature of the mind is to seek defects because it does not easily accept the greatness of others. Given this, of what standard will be the literature created by such a mind? This is the reason one needs to constantly introspect one’s Atman. The litterateur, akin to this self-introspection, must also investigate the subject of his literature. Just as how no commodity is sold without profit, the writer must select a subject that profits both himself and society.

“A litterateur desires respect, acclaim and status. But he thinks he gets it through his books which stir the waters of the society. We have all read in school that water is purified by applying a paste of powdered Nirmal nuts (Strychnos potatorum) to the vessel. This is precisely what needs to happen in the field of literature. If the society needs to profit from literature, the reader must experience joy even for a brief moment. The goal of that joy is the serenity of mind. The mind which is more restless than a monkey and crueller than a serpent must not be further provoked by inducing agitation: Aśāntasya kutaḥ sukhaṁ.

“The other trend among our current writers is to regard money as the ultimate arbiter of success. But there is something far greater than money. Until recently, the British monarch Edward and the Emperor Gautama, thousands of years ago, renounced their throne. Edward abdicated succumbing to the charms of a woman. Gautama renounced in his quest for Inner Peace. Herein lies the difference. Votaries of the West set the acquisition of a woman as their final goal. The goal our people has always been this inner quest, or self-realisation.

“Our people claim that they are the proud inheritors of a profound culture spanning Yugas. If that is true, what is the nature and essence of that culture? How does one imbibe it? These are the journeys that our present writers must undertake. Until then, creating true literature will remain a dream. A bad dream.

“Then there are people who claim that our culture was enslaved by outsiders because it was weak. Kalidasa has answered all such fatalists long ago: kasyaikantam sukham upanatam duhkham ekantato va — no one experiences continual happiness or continual misery. Likewise, literature too gets created whether or not there is Rasa and beauty in it. However, there will be at least some element of Samskruti in all true literature. I hope that day dawns once again in our literature.”

DEVUDU’S MAHABRAHMANA—among other works in his superb repertoire— is the standing monument of this profound theoretical exposition on true literature. He could speak with such unabashed and blunt candour about literature because the literature he had created remains unbeatable. In ordinary or mediocre hands, the extraordinary story of Visvamitra would have ended up as hero-worship at best or a revenge saga at worst. In Devudu’s hands, it became a great Havis (offering) to the Vedic culture of Bharatavarsha itself. Starting with its genesis:

"The impulse to write this novel was born in 1926. By that time, I had realised the glory of Gayatri, and I decided to write the story of the first man who had not only realised Gayatri but had shared it with the world thereby performing the greatest act of benevolence. However, I felt that it was improper to embark on writing about this great Rishi without first undergoing the prerequisite training in the traditional fashion. The Arsha Rna [debt owed to our Rishis] had to be repaid first before writing such a work.

“By 1947, the impulse to write this work had matured, and I began penning it down. It was complete by August 1950.

“Those who have written great works will realize a fundamental truth in their experience: the Jiva within each of us, which is incessantly writhing and yelling, “Me!” “Me!” “I!” “I!” will discard its pettiness and fly high like a seashell and attain a new insight hitherto unavailable to it. It will then fill the heart with this insight and that fullness will emerge in the form of a literary work.” (Preface to Mahabrahmana. Emphasis added)

Speechless when I first read it. Speechless even now.

EVERY SYLLABLE AND WORD AND SENTENCE in Mahabrahamana is a pearl and it is beyond my capacity to do justice to a work which is almost in the Upanishadic league. Or to borrow Devudu’s own words, “the Atma of Bharatavarsha has been depicted in this work…Therefore, for those who think that this is just a story, it is just a story; for those who regard it as a Sastra, it is a Sastra; for those who regard it as Vidya, it is Vidya.”

In our own time, Shatavadhani Dr. Ganesh has given us the best and the most comprehensive exposition of Mahabrahmana in his lectures delivered more than a ago. Not stopping at that, he has also given us a fine Sanskrit translation of the work.

What I can manage is to offer a glimpse from the work, the aforementioned pivotal encounter of Vasistha and Visvamitra. The story is well-known but how the master sculptor Devudu Narasimha Sastry has chiselled it is not so well-known.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.