- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

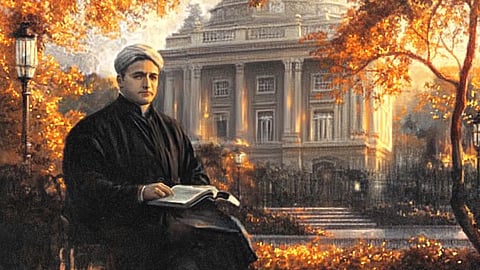

IT IS A PROFOUND REGRET that Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyaya’s immortal Vande Mataram has still not been adopted as our national anthem. While it appears in his novel Anandamath, one of the pathbreaking treasures of contemporary Bengali literature, not much is known about the genesis of the song.

A popular anecdote says that Bankim composed it as a reaction to the British Government’s forcible imposition of England’s anthem, God Save the King as India’s national anthem as well.

However, the most reliable and firsthand story of the origin of Vande Mataram was published in The Hindoo Patriot, a highly influential and widely read English weekly throughout the Bengal Presidency. It was founded by the redoubtable Madhusudan Ray, Girish Chandra Ghosh and Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar.

A twenty-eight-year-old D.V. Gundappa reproduced the full story in his own biweekly, The Karnataka dated 20 November, 1915 under the heading, Anecdotes of Bankim.

The saga of the origin of Vande Mataram is also a primary source for the study of the Indian freedom struggle before the Indian National Congress was even conceived. In less than 1500 words, it paints an inspiring panorama showing the socio-political, intellectual and cultural climate of a Bengal that was throbbing with patriotic zeal, intellectual vibrancy and spiritual fervour.

The following is the full text of the story. Subheadings and paragraph breaks have been added for better readability.

Happy reading!

Ananda Math was composed in the early [eighteen] eighties when Bankim was stationed as a Deputy Magistrate at Chinsura. Here he had gathered around him a small but select band of youthful admirers who adored him and literally hung upon his accents.

Here too, his modest mansion on the river bank was the week-end resort of several leaders of the republic of letters, men who had achieved an assured literary position. Poet Hem Chandra, critic Chundernath Rajkrista, the author of Mitra Bilap and Pundit Ramgati were among the regular visitors, while many other literary men, too numerous to be mentioned, were also in the habit of paying periodical visits to the court of that Grand Napoleon in the realm of Bengali literature. Among the Chinsura companions, Babu Akshay Chandra Sircar was the most brilliant. There were two other gentlemen, one a Deputy Magistrate and the other a Pleader less well known, who often acted as Bankim’s amanuensis, as it was then the practice of the great novelist to dictate to a friend and rarely to put pen to paper himself.

One day Bankim fairly staggered his young friends and companions, to whom he was deeply attached and whose welfare was always nearest to his heart, by announcing his intention to teach them the Sanskrit classics, Kumara Sambhava and Dasakumara Charita. That he was a consummate English scholar everybody knew. That he had begun an English novel in Mookerjee’s Magazine, depicting the life of “Bhubaneshwari — a Hindoo Widow,” was a fact which was only too well known to his Chinsura followers. But whoever had thought Bankim capable of filling the chair of Krishna Kamal Bhattacharjee? The pupils asked when and where Bankim had learned Sanskrit. “At home” was the bold and prompt reply.

But however much they were surprised when they first heard of the proposal, their astonishment knew no bounds when the self-appointed Pandit Mahashaya began his vyakhya and drew forth from his well-stored memory parallel passages covering the entire range of English literature. It was indeed a sight to see the Master in the disguise of a University Don.

Bande Mataram was the off-spring of much thinking and dreaming athwart the silent watches of the starry night. It was not composed until the [Anandamath] volume had been half finished. His companions often taxed him for the delay in composing what was expected to supply Bengal with a National Song. But Bankim sought to curb their impatience by telling them, like Mr. Asquith, — “Wait and see.”

At last the right psychological moment arrived. It was four o’ clock in the morning, the moon was sailing majestically across the heavens. All nature lay asleep and still, save a few night birds and old opium-eaters.

Suddenly the two younger men, who lived close to Bankim’s house, heard a voice and a knock at their door. They got up in a trice and found — Bankim himself, his handsome features aglow with “The light that never was on sea or land, The consecration, and the Poet’s dream.”

[Bankim said]:

“Come, I am now going to dictate the National Song.”

The devoted youths followed the Master to his house and one of them seizing a piece of paper began to write according to dictation. When Bankim had come to “Who says, mother, thou art weak?” both the youths respectfully pointed out that after such a resounding cataract of choice and chaste Sanskrit, the line quoted above seemed to be too tame and ill-matched.

Bankim said that they would live to appreciate that line someday. He added — “I know you won’t like this line, but let Hema come on Saturday next, and I am sure he will not take exception to it.” It so happened that the author of the other and older national song, Ar Ghoomavona, turned up one night earlier and when he read the poem, he declared that nothing sweeter, nothing nobler, and nothing grander had ever been written in any language ancient or modern, — an estimate which every Bengali will lovingly and reverentially endorse.

As an executive and judicial officer, Bankim was unsurpassed. Commissioner Beames swore by him and Grant, the District and Sessions Judge, seldom upset a judgment delivered by Bankim. In him there was a rare combination of tact and sterling independence.

At first there was little love lost between Bankim and Bhudev. We think the latter drew a higher pay as a senior officer of the Education Department than did the former as a Deputy Magistrate. At any rate there was no social intercourse between the two giants though they were neighbours.

One day as the two aforesaid companions of Bankim were taking an afternoon walk, they met Bhudev who playfully asked them whether the nocturnal assemblies at Bankim’s place where there was supposed to be as much flow of whisky as of soul, still continued till the small hours of the morning. They replied that Bankim Babu was then in great mental distress as his twin grand-children upon whom he had lavished all the wealth of his affection, had got something wrong with their eyes and their grand-father was consumed by anxiety on that account.

Hearing this, Bhudev said that the ladies of his family knew of certain tried remedies which were very efficacious in such cases and that he would send them to Bankim’s house that afternoon to see the children.

The news was immediately conveyed to Bankim who, overjoyed at this unexpected condescension, on the part of one whom he had hitherto regarded as being too proud to recognize him, at once rushed into his Zenana and gave his wife certain instructions as to how the visitors should be received. The remedy proved efficacious and thus the foundation of friendship and mutual regard was laid between Bhudev and Bankim.

Now a few words as to Bankim’s partiality for the bottle, especially as exaggerated stories had been circulated by detractors. Bankim never got drunk, but only became a little bit lively in his conversation, lit up, as it always was, with flashes of wit and wisdom.

Once his friends entreated him to abstain from touching liquor only for a fortnight, expecting that after that period he would be able to resist his craving for drink. He agreed to do so and faithfully kept his word. But on the sixteenth day the Old Adam in him asserted himself and he announced his determination to return to the bottle.

To prevent him from drinking on that day his friends had invited him to a dinner that evening to a place where no liquor could be had either for love or money. Bankim had anticipated this move and taken with him a phial containing sufficient liquor for that evening.

His company indeed constituted a liberal education. No man came into constant contact with the Great Wizard without being benefitted by a quickening of his intellectual faculties and a broadening of his outlook on life.

To those who were privileged to enjoy his society, the memory of those never-to-be-forgotten days will ever abide as their most priceless possession in life.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.