- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

MAHA SHIVAN BEGAN STUDYING MUSIC under the guidance of his father and other musicians in the village, but was soon sent to Manambuchavadi Venkatasubbiah. He was the foremost teacher of the age, who had studied under the great Tyagaraja himself. Among the trinity of Carnatic music, Tyagaraja is regarded the first among equals.

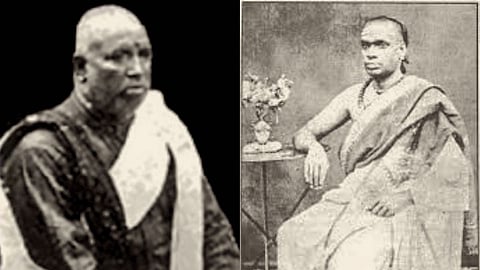

In this sense, Maha Shivan was directly in the line of Tyagaraja’s tradition. But his style was his own and had little in common with the other great pupils of Venkatasubbiah, notably his great contemporary Patnam Subramanya Iyer (1845 - 1902). It is possible that Patnam was closer to Tyagaraja in style and execution, while Maha Shivan had evolved a unique style based on his capability of both styles. Patnam and Maha Shivan carried forward different aspects of it.

Patnam once highlighted the difference between the two to his student Vasudevacharya of Mysore: “You see Vasu, one must evolve a style that suits one’s voice. Can I sing using the rapid tempo of Maha Shivan? No! Can he sing compositions emphasizing moderate tempo and variation the way I do? Again, no! Why? Because our voices are totally different. A good musician always sings in a style that is natural for the voice.”

Patnam’s style – also taking root in Tyagaraja – has come down to us. He was the foremost teacher of his day, and the singing of some of his students’ students is available on records, and the students still performing Maha Shivan’s style are more elusive. He sang at an extremely rapid tempo. What was druta (fast) for others was his beginning tempo, but there was no distortion or dropping of notes. Vasudevacharya writes: “Every note, every syllable and word were clear even at the highest tempo. Each passage was like a string of dazzling brilliants. His creativity in swara-kalpana [improvised passages] was astonishing. At the same time, his singing was clarity itself and left the audience in a state of trance.”

In other words, his singing was full of fire – both in creation and execution. Recognizing this, his great contemporary Patnam, only a year younger and his life-long colleague, had cultivated the totally opposite style of moderate tempo and unhurried exposition. This also suited his easygoing temperament.

The two artists, total opposites in style and temperament, were the foremost singers of the second half of the nineteenth century. There were many other outstanding musicians – both vocal and instrumental – making it the golden age of Carnatic music. It drew its inspiration from the burst of creative genius of the Great Trinity of Tyagaraja, Muttuswamy Dikshitar and Shyama Sashtri in the late eighteenth and the early nineteenth century.

As previously noted, this creative burst was made possible by innovations in music theory and performance beginning with Purandara Dasa. It is interesting that the Great Trinity was contemporary with Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, which gave Europe its own Classical Age.

To return to Maha Shivan’s style, one can try to get some idea of it from his students. Patnam sent some of his advanced students to Maha Shivan to polish up the Kalpana-swara singing. One of them was Ramnad Srinivasa Iyengar (or ‘Poocchi’) who sang in this century. It is said that his singing had echoes of Maha Shivan’s style. The same cannot be said of Poocchi’s foremost pupil Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar who sang well into the fifties and is available on records.

One of Maha Shivan’s major students was Konerirajapuram Vaidyanatha Iyer who left behind a great student – Maharajapuram Vishwanatha Iyer. Perhaps in Maharajapuram in his glory days, we can hear the style of the master, especially in Kalpana-swaras. There are times when I feel the that the modern singer Balamuralikrishna, with a style all of his own, has mysteriously imbibed some features of Maha Shivan’s style, though vocally the two cannot be compared.

An unusual feature of Maha Shivan’s recitals was that they were short by contemporary standards. In an age when people thought nothing of three-hour programs, Maha Shivan rarely sang for more than an hour and a half.

For one, he began his program at full tilt, without the warm-up pieces that other singers use before getting to the main part of the program. His voice allowed him to do that. His style, which wasted no time on non-essentials, ensured that the full length of the program was devoted to the best music. The emphasis was on mano-dharma or ‘creative music’, where compositions of Tyagaraja and Dikshitar were used as vehicles for the exposition of a particular raga. The latter part of the program was devoted to his own compositions. His rapid tempo and fiery style covered more musical ground than others did in programs twice the length. The highlight of his program were alapanas and tana or rhythmic variations, and Pallavi or singing variations around a basic text followed by Kalpana-swaras.

Above all, it was the creativity displayed in his mano-dharma sangita that made him stand head and shoulders above his contemporaries. It may be argued that even without his extraordinary voice, his creativity and musical scholarship would have ensured his supremacy. His Kalpana-swaras were so extraordinary that musicians copied down his extempore creations and adopted them as part of existing compositions. They are still in use as part of some of the most popular Dikshitar compositions.

Not one music fan in a hundred probably knows that some of the best parts (sangatis) of famous Dikshitar compositions like Vatapi ganapatim bhaje’ham (Hamsadhvani raga), Chintaya ma kandamulakandam (Bhairavi raga) and others were introduced by Maha Vaidyanatha Shivan in his performances and were not part of the composition. These have now become part of the composition. It may be said with justice that the popularity of Dikshitar’s muic owes as much to Maha Shivan as to the Dikshitar. 16 They give us a glimpse of his creative genius as a performing artist. For one, Dikshitar’s works were not widely known in the 19th century before Maha Shivan introduced them. In addition, Dikshitar did not leave a major school of performers as Tyagaraja did. There is no Dikshitar school or parampara to compare with Tyagaraja’s, which stemmed from his students.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.