- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

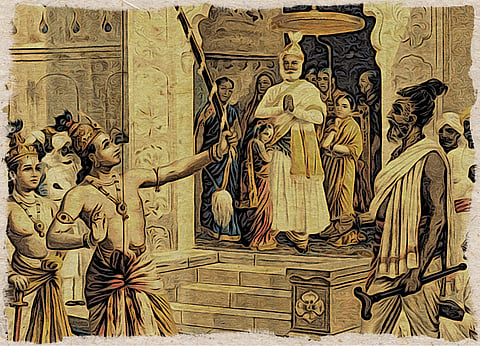

The luminous hallmark that reveals itself even in a preliminary study is the remarkable antiquity, unrivalled continuity, sturdy endurance and intrepid resilience of Sanatana statecraft and polity. With a recorded history of over two thousand years—dating back to at least the 4th century BCE—this tradition endured and retained the core elements of its original glory till the downfall of the Maratha Empire. The full text of Chhatrapati Shivaji’s coronation offers a panoramic delineation of the glory of a true Sanatana Samrajya ruled by an uncompromising, rock-solid Kshatriya.

However, the full fiendish disgrace for wiping out the last vestiges and even the living memory and traces of Sanatana statecraft and polity undoubtedly goes to Indira Gandhi who abolished privy purses and criminally betrayed Sardar Patel’s trust. As a rough history experiment, one can consider the regions ruled by the (nominal) Hindu princes from the British colonial period up to the abolition of the privy purses. The conclusion is inescapable: it was in these regions that age-old Hindu customs, traditions, and festivals were preserved largely in their original forms. The last surviving element of this historical fact is visible in Mysore Dussehra, which is a Hindu festival, not a tourist attraction.

The primary and recommended approach for studying Sanatana statecraft and polity is to desist the invariable urge to compare it with western democracy for three important reasons.

The first is the selfsame antiquity; that is, Indian polity and statecraft evolved gradually over more than a millennium. By the time Europe emerged from its soul-eroding Christian Darkness, Bharatavarsha already had a well-rooted and firmly established political tradition which did not rely on One Holy Book to deliver justice in the material world. Above all, this political tradition had inbuilt mechanisms for safeguarding and ensuring cultural continuity. Throughout its evolution, the Sanatana political system faced ebbs and tides but never abandoned its foundational ideals, aims, and retained its core strength till the time of the Marathas and Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

The second is the fact that research done by early Western scholars in this field is winnowed with defective scholarship. Writers like Max Mueller, Weber and Roth ignored or were unaware of or casually bypassed the mind-blowing corpus of literature on statecraft in Sanskrit, Pali and most major Bharatiya Bhashas. We highly recommend reading the introduction in R. Shama Sastry’s classic Arthashastra in which he performs a thorough surgery of such Western scholarship by naming and shaming the scholars.

The third reason relates to the spirit. There is no realistic reason Indians should feel inferior to or ashamed of a comparison between Sanatana and Western political systems. On the contrary, we should welcome it provided truth is the only yardstick of this comparison. Let’s not forget that democracy was “granted” to India in two major phases: first by a pitiless commercial exploitation, and then by military and political colonisation. The sham democracy India experienced roughly beginning in the 1920s up to 1947 was primarily subject to England’s whim and not to its supposed civilised benevolence.

This backdrop is essential for a standalone study and assessment of Sanatana polity and statecraft from the earliest times.

For a start, we can’t find a more illustrious sage than D.V. Gundappa who drank deeply from the profound fount of the founding ideals of Sanatana ethos of whose infinite bounty polity was just one of the outward expressions. His treasure-trove of writing repeatedly invokes the Ashwamedha Yaga portion of the Taittiriya Brahmana of the Yajur Veda, which he correctly calls as the National Anthem of the Rishis.

Let us be bestowed with auspiciousness, safety, security, and abundance. Through this Yagna, may the citizens be blessed with unity and peace.

And DVG was our contemporary colossus (he passed away in 1975). The fact that he regarded this Vedic hymn as one of his primary political ideals in the 20th century is Proof #97348937479324732932 of the aforementioned sturdy endurance. Neither does he stop at that. Even as Nawab Nehru was thundering his fatuous nonsense at midnight in Delhi about an alleged tryst, in faraway Basavanagudi in Bangalore, DVG penned an inspirational, moving poem in the quietude of his room: alone, elated but anxious for the future of an “independent” India.

His worst fears have come true in a nightmarish fashion.

In the Sanatana annals, polity and statecraft in both theory and practice is familiar by the terms, Rajyasastra or Rajadharma. However, other synonyms—some well-known—exist: Arthasastra, Dandaniti, Nitisastra, Rajaniti, Rajanitisastra, and so on. Indeed, Arthasastra has been synonymous with Dandaniti from the earliest times. This then is the other blight. The calculated destruction of Sanskrit in “independent India” has rendered us inaccessible to ourselves, an unforgivable self-inflicted cultural holocaust that is both unprecedented and unparalleled. One vainly hunts for words to describe the phenomenon where a vote is taken to decide whether we must preserve our own culture and language.

According to the Sanatana tradition, Saraswati Devi gave Danda Niti to this world, which is quite befitting when we think about it.

Keshava [Vishnu] armed with an enormous Sula [spear], created his own self into a form of chastisement. From that form, having Righteousness for its legs, the goddess Saraswati created Danda-niti (Science of Chastisement) which very soon became celebrated over the world… Chastisement should be inflicted with discrimination, guided by righteousness and not by caprice. It is intended for restraining the wicked. Fines and forfeitures are intended for striking alarm, and not for filling the king's treasury.

Mahabharata: Shanti Parva: Section 122

The primary goal and function of Danda Niti is that it should act as the “support of the world” by establishing order and checking and punishing evil. The Raja or king is the upholder of Danda Niti. It is his primary Dharma.

At the broadest level, Raja Dharma has a twofold goal:

1. The Ultimate: As a means of attaining Moksha through virtuous deeds, etc.

2. The Proximate: To create and maintain a condition of sustained peace, safety, stability and ensure the freedom of vocation, right to enjoy personal property, to safeguard the traditions, customs, etc of every clan, guild and sect, and to deliver speedy justice.

Technically speaking, although the king was the master of all land in his domain, he was merely a trustee, and individuals had full property rights. The Nanda dynasty violated precisely this sacred tenet, a crime that deserved the severest punishment. The classic TV series, Chanakya powerfully describes the nature of this violation in this pithy dialogue: “iss dharaa ko apne daasi samajh baite hai” (these people have treated this sacred Mother Earth as their personal maidservant).

The implication is clear: it is only in Bharatavarsha that Arthasastra is subservient to Dharmasastra. Indeed, Arthasastra texts and commentaries unequivocally state that Dharma is the highest goal, a constant theme constant. For example, the Kamasutra says that Kama is the lowest of the three Purusharthas and Dharma the highest.

Invariably, every exponent, scholar, writer and commentator on Arthasastra sounds this refrain: when clashes or conflicts in worldly [Artha]transactions cannot be resolved by law, custom or usage, the verdict of the Dharmasastra prevails. This timeless and perennial primacy of Dharma is what preserved our civilisation. Innumerable Hindu Empires flourished and fell but the Sanatana civilisational spirit has survived. To that proportional extent, our culture and traditions have been preserved.

On a very profound plane, Dharma exists not for its own sake; in fact, such a notion is itself absurd. Dharma achieves nothing by serving itself akin to light illuminating itself. Its presence is intangible and therefore unenforceable by the writ of a king or president. Dharma is both an ideal to be realised and a value to be cultivated in our inner lives and pursued in the outer. There’s a reason Dharma is the first Purushartha, and blessed is the person who realises the straight line leading from Dharma to Moksha by bypassing the avoidable tumults of Artha and Kama.

Without realizing Dharma in both its changeless and dynamic states, we will get the Western (or Islamic) political and social condition of constant one-upmanship and endless strife. Political life or politics is merely an instrument (Sadhana) to attain a higher state of life, and not an end in itself. We shall examine this theme in the next part of this series.

There was a reason our great Hindu Empires survived unbroken for five, six and even seven generations: by realising Dharma in the realm of statecraft, they ensured stability and bloodless succession. The point becomes crystal clear when we contrast it with Muslim dynasties which were as strong as their strongest sultan. The sickening motif of a sultan’s son murdering his own father only to capture political power is more a rule than an exception in the Muslim history of India.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.