- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

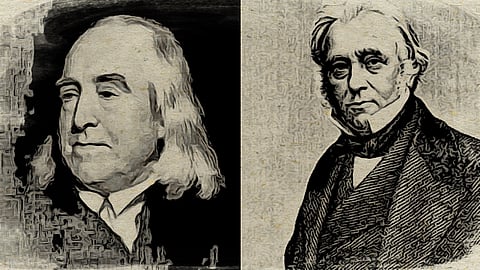

Thomas Babington Macaulay’s comprehensive vandalism of the unbroken educational heritage of India wouldn’t have been so phenomenally successful but for the unstinted official support he got from William Bentinck, then the Governor General of British-occupied India. By any standard, Bentinck remains a gold-standard robber baron of an epic scale. Bentinck’s cruel disruption of the centuries’ old education system of India is a devastation that we will perhaps never recover from.

Indeed, by the time he was just thirty, the tree of evil had grown monstrously within Bentinck. As a young Governor of the Madras Presidency, Bentinck wrote to Lord Castlereagh in 1804 that, “we have rode the country too hard, and the consequence is that it is in the most lamentable poverty.” It was not remorse but a realization that the bleeding of India at the “point of the bayonet” was not good for the East India Company in the long term. More effective and calculated measures were required.

In total, these measures included a systematic breakdown of traditional Hindu institutions and the one great tool that would aid him in this endeavor was education. These are roughly the origins of what is known as the British education system, which we are faithfully following till date. The rotten core of this kernel remains unchanged. Only the external paint has been changed from time to time.

Bentinck’s vile project was ably assisted by what I call the racist Quartet: Thomas Babington Macaulay, Charles Trevelyan, Charles Metcalfe and Mountstuart Elphinstone. It is unnecessary to dig out the details of what this Quartet said and did as handmaidens of Bentinck but their actions culminated in the English Education Act of 1835. English became the official language of India, a status it enjoys even today minus the unofficial patronage. This is the purest form of how colonization succeeds even when it no longer enjoys political clout.

Think about it. For the longest time after India attained “independence,” the British Council offices and libraries in Indian cities remained a powerful, unofficial visa for Indians to “a better life.” Did you find a single work of Sanskrit or any Indian language in the British Council library? In reality, organisations like the British Council are the softcore foreign policy arms of the British Government, a method of affirming a sense of colonial permanence in their former colonies. In all my travels abroad so far, I am yet to see even a droplet of this sort of farsighted and far-reaching foundations of India’s foreign policy. To put it bluntly, our alleged cultural embassies abroad are slightly better than a joke. For the longest time, they were dens for our IFS and other Babus to cultivate tiny islands of personal privilege and acted as gateways for securing the future of their children. Perhaps that is changing now, perhaps not. That is a topic for another day.

The English education system that William Bentinck implemented has another central fact that few have cared to examine: it was not merely English education as a language and a medium of instruction, it was also Church-centric. The following are listed as among the common “benefits” that English colonial rule brought to India: railways, postal services, mass healthcare and mass education.

The Church was the first to sniff the great opportunity for soul-harvesting that was innate in healthcare and education. Look around you even today. There is not a single Christian-run hospital or education centre that is not affiliated to a Church of some denomination. Indeed, minus the imperial British patronage, this alleged education wouldn’t have had such widespread cancerous growth in India.

Bentinck’s deadly project began to yield fruits quite rapidly but it also met with stiff opposition. The first wave of opposition came quite naturally, from Bengal, the original hub of British conquest and power in India. By the later part of the 19th Century, the Bengali Hindus began to publicly show their contempt for the British system of education and began to call the schools and colleges controlled by the Calcutta University as Gholam-Khanas (factories manufacturing slaves).

On the other side, the greatest victims of Bentinck’s heartless sword were the traditional Sanskrit schools and colleges ( pāṭhaśālās) of Bengal that had flourished for centuries as extraordinary centres of learning, easily comparable to the best ones at say, Varanasi. In one stroke, hundreds of these Sanskrit learning centres were obliterated.

One such eminent institution was the Goḻiśrī Saṃskṛta-pāṭhaśālā (Golishri Sanskrit School) in Calcutta. Until Bentinck arrived with his cultural chainsaw, this school was patronized by and recognized as an institute of excellence in Sanskrit education even by the European Indologists and Sanskritists of the period. H.G. Wilson, the British Sanskrit scholar was one such patron. He had established and encouraged this pāṭhaśālā and was instrumental in appointing teachers and Vidwans into its folds.

The head the Goḻiśrī Saṃskṛta-pāṭhaśālā, Premachandra-Vagisha felt as if lightning had struck him when he heard that Bentinck had decided to close it down. He wrote several anxious letters to Wilson who was in England then. The letters were verses penned in exquisite Sanskrit and is enough to melt the hardest stone. The following is a prose English translation of these verses.

This is the Sanskrit college which you established and it is akin to a lotus-filled pond. But now, all the scholar-swans have gone away having lost their patronage. Hunters lie patiently in wait on its shores, their arrows aimed at us. They are merely waiting for the right moment to shoot. If you protect us from them, your fame will become immortal.

Wilson’s reply likewise, was in verse. He spoke in quasi-reassuring terms and praised the glory, greatness and immortality of Sanskrit, the “language of the Gods” but offered no concrete solution. In itself, this shows how in a naked imperialism, even renowned scholars are essentially powerless before a ruthless might. However, Premachandra-Vagisha was dogged. He repeated his plea in another set of moving verses saying,

This Sanskrit college is situated in the middle of sylvan greenery in the city of Calcutta by the side of the Golishri Lake. It now resembles a timid and innocent deer. Fate has dealt it a cruel blow. Macaulay, the merciless hunter is just about to shoot it with his sharp arrows. O Wilson! This frightened deer is making an earnest appeal to you with tears in its eyes, pleading for help in your name.

Wilson’s reply this time was along the previous lines. We are unaware whether Wilson did indeed try to save the Goḻiśrī Saṃskṛta-pāṭhaśālā but what we know for sure is that this Sanskrit school was pitilessly erased from history.

All because Macaulay and his racist British mafia in all their arrogance decided that “a single shelf of good European literature was worth the whole of native literature of India,” and that “all the historical information which has been collected from all the books…in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgements used at preparatory schools in England.” What is more amazing is the fact that Macaulay passes this judgement after admitting that “I have no knowledge of either Sanskrit or Arabic.” Certainly. But he had full knowledge of the workings of imperialism of which he was a willing slave and substantial beneficiary.

These are the real stories of India’s continuing tragedy also known as history. When these are taught to our children, the other peripheral details of places and timelines will automatically fall in place. Meanwhile, we wait perhaps with vain. And with a sliver of hope.

For the heart-wrenching tragedy of the Goḻiśrī Saṃskṛta-pāṭhaśālā, we’re indebted to Shatavadhani Dr. Ganesh’s fine compilation, Kavitegondu Kathe or Stories Behind Verses, which can be purchased on Amazon.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.