- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

Of the countless invaluable cultural heritage that Santana Bharata has lost irretrievably, perhaps nothing is more profoundly tragic than the stories that our own people, real people, told about themselves and their ancestors. Indeed, worship of ancestors, Pitrs, is a distinctively unique cultural trait of Sanatana civilization not found in any other culture. The mad rush to blindly embrace what is known as “scientific” history has proven to be a fatal death-kiss as far as these stories are concerned. Arguably, the greatest beneficiaries of this “scientific” history have been our Marxist cultists who are now scientifically “proving” that Algebra is oppressive.

Sanatana history preserved in what is dismissively known as “oral legends” and “folklore” is almost dead. At least until the mid-1970s, India still had old men and women who remarkably preserved the memories of their ancestors on their tongue-tips. To them, these were not legends or fables or fiction but the continuation of lived, real lives brimming with the immutable value that only centuries of tradition can bring. Time has taken away tens of thousands of such old men and women and they have taken their stories with them. Not even a fraction has remained. And what has remained is unknown in a public discourse that is alien to itself.

No amount of Oral History Projects can rescue this pathetic state of affairs because the keyword here is “project,” not “life.” The Sanatana conception of Itihasa (history) is a continuum, not a mere record of a dead past. To put this in Nietzsche’s words, if you stare at a historical document, it simply stares back at you. Which is why our people emphasized on telling stories of real people—their lives, loves, fears, heroism, passion, compassion, intensity, magnanimity, loyalty, devotion, and truthfulness in a brutally frank manner. Majority of these stories reveal the same trait: Hindus as a civilizational people were the most heroic and the most evolved because their Vedantic sculpture of life enabled them not to fear death but to welcome it, embrace it. If a perverse tribute was needed, it is available in the voluminous annals of Muslim and other alien histories who were baffled by this absolute fearlessness in face of death.

This heroic DNA operated even in the realm of Gods. The same Purohitas, Archakas, Yogis, Sadhus, Sanyasins, and Babas who have now become easy targets for casual humiliation and mockery by Hindus themselves once commanded reverence from the entire society because they toyed with and even commanded our Devatas. And the Devatas obeyed them. The aforementioned legends and folklore abound with such stories of such real people.

Here is a sample from the prolific Kannada novelist, T.R. Subba Rao’s acclaimed Hamsageethe (Swan Song). The following is an abridged retelling of the essence of a slice of the novel.

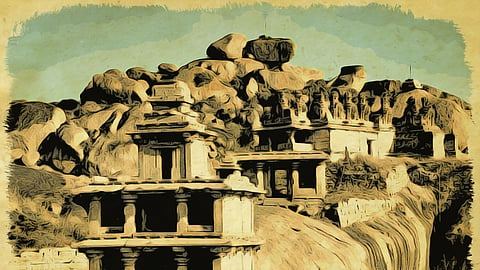

The story is set in the regime of the indomitable Madakari Nayaka, the last Palegar of Chitradurga. It narrates the exalted life of Veeranna, the Archaka of the Hidambeshwara Temple situated in the sweeping precincts of the majestic hill-fort of Chitradurga. Like his ancestors, Veeranna was a spotless devotee of Shiva whose Puja he performed twice a day in the temple. As part of daily routine, the Palegar would visit all the temples in the fort in the morning and evening for Darshan, take the Prasadam and then return to his palace. The bugle would sound from the top of the fort announcing the departure of the Palegar. This was an indication for all the Archakas to get ready. The routine was set in stone and functioned like clockwork.

Veeranna had a small weakness in the form of a concubine who he was greatly attached to. Akin to a second wife, their relationship dated back to several years. After the evening Mahamangalarati, he took flowers and fruits and some offerings to her. Life went on in this manner until that fateful night.

Veeranna had made all the preparations for the Mahamangalarati and patiently waited for the Palegar’s arrival. The bugle didn’t sound at the usual hour but he waited. Perhaps the Palegar was busy. Perhaps he was indisposed. He waited. Then the midnight bell sounded from the Kotwal’s quarters. The Palegar had still not arrived. Finally, Veeranna performed the Mahamangalarati, waited some more time and finally left for his concubine’s home. As usual, he carried fruits, flowers, milk and other items and reached her home. He decked her with flowers, had some dinner and prepared to sleep.

The bugle sounded.

Veeranna shuddered a little. He had violated the law: that all the Archakas had to stay in the temple till the Palegar took his last Darshan and Mahamangalarati of the day. He also knew the Palegar well: that he could be as merciless as he was generous and compassionate. From the depths of his heart, he regarded Archakas and other holy men as Devatas who walked on this earth and sanctified it. And they had to conduct themselves accordingly. Even a slight lapse in their conduct would mean instant beheading.

Frightened out of his wits, Veeranna took the flowers he had decked his concubine with, put them in a bag and rushed back to the Hidambeshwara Temple. He redecorated the Deity with the flowers, readied the Mahamangalarati and waited.

The Palegar arrived with family and retinue. Veeranna performed the usual Puja, Archana and gave him the Tirtha and Arati. The Palegar took the flowers and was about to touch it to his eyes, he noticed a long, clear strand of hair and paused. He neatly separated the hair, held it up for everyone to see. It was unmistakably a woman’s hair. His expression became grim and his tone was like a hammer when he spoke:

“This flower is part of the Prasadam you have given. Where did this hair come from?”

Veeranna shivered but didn’t show his fear. He said in a tone of defiance:

“It is from the Deity’s matted locks.”

“Really? Which Deity?”

“Who else? Hidambeshwara.”

“Since when did the Exalted Archaka learn to speak untruth?”

“If this tongue has spoken untruth, may it be slashed and fed to dogs. This body has eaten the food Hidambeshwara has provided. This life is His. It doesn’t know how to lie.”

“Indeed. His Eminence doesn’t know untruth yet by some miracle, Hidambeshwara has suddenly grown hair.”

“I have told you once Your Highness, and I’ll tell you again. Lying is not something I have learnt.”

“In that case, this stone Lingam has matted locks.”

“To your sight, it is a stone Lingam. Not to mine.”

“In which case, can We see the matted locks?”

When the Palegar uttered these words, anger was palpable in his voice.

Realizing the dangerous extent to which this exchange might escalate, one of the Palegar’s close advisors said,

“Your Highness, one must not undertake such kinds of investigations related to the Devatas. Perhaps Your Highness is unable to see what the Archaka can clearly see. We can leave this matter at this.”

But the Palegar was adamant.

“If We can see a strand of Hidambeshwara’s hair we can surely see the full lushness of His matted locks. Right? If the Exalted Archaka has indeed lied to me, it is perfectly fine but is it fine if he lies in the Deity’s matter as well? He could have claimed it was an oversight or that the flower had fallen somewhere and this hair had gotten mixed up as a result…there are a hundred such possibilities. But why is he so obstinate to insist on this kind of thing?”

Veeranna’s stubbornness had now become like a rock. He said:

“Indeed, I insist. It is up to His Highness to believe or no.”

“In which case, let the investigation begin. I’ll see it with my own eyes.”

“As His Highness pleases.”

“And if the matted locks of Ishwara are not found on the Lingam…”

“The King can gladly chop my head.”

The Palegar looked at Veeranna’s face. There was no trace of hesitation let alone fear. His expression was resolute, decisive. Everyone present in the confines of this cave temple were frozen. At last, the same advisor broke the icy silence:

“I beseech both of you again. This sort of investigation of the Divine doesn’t augur well for anyone. The Mother of the Universe, Kali herself appeared before Kalidasa each time he wrote poetry. Saraswati danced before our great singers. This doesn’t bode well.”

But the locked battle-horns wouldn’t budge. But because it was already late, and the Palegar had to visit other temples, the time for the investigation was fixed for the following morning. Besides, the present audience largely consisted of the royal family and high-ranking people. The divine investigation would have meaning if it was conducted in the presence of the common people of the kingdom.

After the retinue left, Veeranna headed for the pond in the fort, immersed himself in the water and stood knee-deep for a while and in wet clothes headed straight for the Hidambeshwara Temple. He sat before the Deity, his gaze straight and unswerving. Then he closed his eyes and addressed Hidambeshwara:

“You made me utter those words. You must keep them. You must keep your own honour. You know that from the beginning I have reposed my everything in you. You know that there has been no lapse in my devotion to you. If you let go of my hand today, let my head fall.”

He didn’t know how long he had kept his eyes closed. When he opened them, there was a bizarre sort of contented satisfaction on his face. He took out a dagger, did Archana with Kumkum to it, showed it to Hidambeshwara and said, “Show me your matted locks or take my head.” Then he closed his eyes again and began meditating. He opened them when he heard the sound of the early morning bugle.

And then he saw something else right before him. Atop the Hidambeshwara Lingam, a snake had appeared, its hood fully open. It swatted a flower down and slithered away. An auspicious omen.

Veeranna got up, went home, had his bath and completed other morning rituals at home and returned to the temple.

The Palegar arrived as usual for the morning Puja and Arati. By now, news of last night’s challenge had spread like wildfire in the city below. A huge crowd had collected outside the Hidambeshwara Temple.

The Palegar asked him pointedly:

“Can we please have our Darshan?”

“May it please His Highness. Certainly.”

Then there was the question of whether the Palegar could enter the Sanctum Sanctorum. Veeranna himself said:

“His Highness has already expressed his wish to test. Please step inside.”

But the Palegar hesitated:

“Are you sure? Wouldn’t we dilute the sanctity by stepping in?”

“May it please His Highness. The sanctity was defiled the moment His Highness expressed doubt.”

The Palegar felt as if someone had delivered an open-handed slap. He turned to another Purohit standing nearby and said:

“Can’t you step in and check?”

The Purohit said gently: “The eyes that expressed suspicion must also clarify it. Please forgive me Your Highness.”

There was no turning back now. The Palegar lifted his jittery legs and entered the Sanctum Sanctorum. Veeranna stared at Hidambeshwara once, prostrated before Him and said a silent prayer: “Hidambeshwara, show me your matted locks.” Then he stood up, parted the flower garlands atop the Lingam and signaled to the Palegar. With trembling hands, the Palegar touched the top of the Lingam. Hair. Yards of them. Miles of them. The infinite tresses that in one stroke had imprisoned Ganga herself.

The Palegar immediately withdrew his hand as if a serpent had lethally bitten him. Veeranna said:

“Please check Your Highness. Who knows, I might have pasted artificial hair. Please check again, please, please please…” his voice rose in passionate devotion as he walked towards the Lingam, held a fistful of hair in his hand and yanked it violently. A massive clump of those lush tresses broke loose as he held it up in the air for everyone to see.

Blood spurted out from atop the Lingam and flowed copiously. Hidambeshwara had performed an Abhishekam of blood to himself.

Veeranna shrieked, “Swami!” and then looked at the Palegar and said, “Hope His Highness is satisfied now.” And then he fainted before Hidambeshwara, his unstoppable tears wetting the floor, merging in Hidambeshwara’s blood.

The stunned crowd exclaimed in unison: “Shiva! Shiva!” The trembling Palegar prostrated before the Deity and one of the Purohits said, “His Highness may please leave. There won’t be any Puja today.”

Expectedly, it took a long time to disperse the crowd, which had witnessed this divine miracle.

Veeranna regained consciousness after a few hours. He felt fresh. Liberated. He stood up and locked the Sanctum Sanctorum behind him. Then he took some Vibhuti, spread it across his forehead, and looked straight at Hidambeshwara face and spoke, weeping like a small child:

“Swami, you battered your head to save mine. How can I even serve you from now on? You bled for my untruth. This life has become filthy because of the vilest kind of lie. You have protected my head by showing yours. Here, I give it back to you.”

Veeranna took the dagger that he had sanctified the previous night, prostrated again and sliced his neck off. In minutes, the Sanctum Sanctorum had transformed into a tiny pool of his blood.

When the worried people forcibly opened the door much later, they were immediately greeted by the overpowering fragrance of the Ketaki flower.

The repentant Palegar installed a stone sculpture of a Veeranna holding his severed head in one hand and a dagger in the other. He left a grant to conduct annual Puja to him.

The story ends here.

The Hidambeshwara Temple still stands in the fort of Chitradurga. The last time I visited, regular Puja was still being performed. I don’t know what the present condition is. It is left to our wisdom whether we wish to visit it as tourists or pilgrims.

Postscript

If this is not history, I have no use for what passes off as history. This adds lustre to life and provides succour to the soul. Dates and hairsplitting over peripheral matters fall in a separate realm and they have their own importance. Our fond hope is that such peripheries should not devour even the remnants of such real stories.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.