- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

THE 2014 AND 2019 ELECTIONS decisively bombed the Congress template of doing politics in India. With that, its ecosystem comprising a rogues’ gallery of Jihadists, separatists, missionaries, and breaking India forces of every hue and tinge continues to remain in tatters. However, at a very fundamental level, the overall national climate that the Congress has created and nurtured over a century has not changed in its essentials. In fact, this is one climate change that is sorely needed. A defining feature of this climate is a weakness of spirit stealthily induced by Mohandas Gandhi. Our own era is witness to the truth that weakness on the plane of the spirit eventually leads to treachery on the national plane.

As we have explained in this series, the history of the Congress Party can be broadly divided into five categories.

In fact, it is surprising that the full history of the Congress Party is yet to be written with the objectivity and critical scrutiny that it merits. Especially, the period in which Mohandas Gandhi dominated not only the Congress Party but profoundly transformed the national psyche for the worse with emotional blackmail as his nuclear warhead. Such a history gives us perhaps the surest key to usher in the aforementioned climate change.

The staggering ascent of Gandhi was naturally accompanied by embracive changes both in the structure and functioning of the Congress. Debate and dissent were replaced by unwilling consensus, which was enforced by fear of non-violent retribution. Gandhi was a lone martyr but Gandhi’s martyrs are in legions.

One such sweeping change was the emergence of the All-India Congress Committee (AICC) and the Congress Working Committee (CWC) as a semi-tyrannical body. Ever since, the CWC sustained its despotism till the final downfall in 2014. As we continue digging some rare archives that we have procured at The Dharma Dispatch, each new excavation gives us clues to more material and unsurprisingly, every finding is distasteful to say the least.

Here are some excerpts of the working of the Gandhian CWC described by Nirad C Chaudhuri. Some formatting changes have been made.

A meeting of the All-India Congress Committee might be likened to a shareholders’ meeting of a great company. Secondly, there was to be a meeting of the Working Committee of the Congress, consisting of twelve members and the President, which was like a directors’ meeting. The discussions at the former were always public, and in the latter always private.

I have next to describe the Congress Working Committee and its members. They were twelve in number, whether in imitation of the Apostles or not I am unable to say. But they were the leading members of the Congress Party. Congressmen had got into the habit of describing themselves in very grandiloquent political terminology. For instance, even Mahatma Gandhi, in writing to a President of the Congress, would call the Working Committee his ‘Cabinet’. The public and the Press called it the ‘Congress High Command’, adopting a military and not civil terminology.

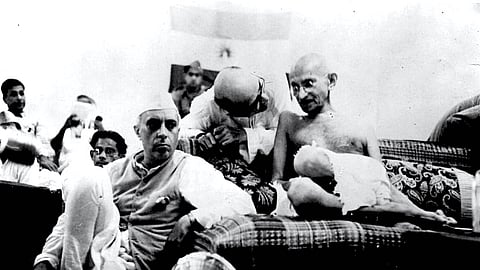

I had a very good opportunity for observing the appearance and expression of all the front-rank Congressmen. Mahatma Gandhi was never a member of the Working Committee. But he hovered above it like the Holy Spirit, and sometimes even descended in the form of the dove of peace. As these important men arrived I took note of them, and compared my firsthand impressions with the idea of their features and faces which I had been piecing together from pictures.

The first impression of the Congress leaders that I received from my visual experience was one of physical unattractiveness. With the exception of one or two, none of them could be described as handsome or even physically imposing. In this the leaders of the Gandhian era were the opposite of those of the pre-Gandhian period. From 1885 to even 1918 they were as a rule, handsome men, with expressions which were both intelligent and urbane. The new leaders showed none of these features.

But what was strange was that in their physical insignificance they were not merely Gandhian. I have said that nobody upon seeing Gandhi noticed his features. In his followers, people would notice nothing else. The faces of all of them had a hard, worldly look, yet without the outward enamel which one could see on the faces of the high-ranking Indian officials, who were even more worldly.

Yet this unattractiveness was the least unattractive quality of the outward appearance of the Congress leaders. They repelled, instead of merely failing to attract. What struck a beholder most forcibly in them was an overweening expression of arrogance, which coated their faces and seemed to be like make-up on cheeks and foreheads. They possessed the haughty air but without any smooth outward unctuousness.

Over and above, their manners, in dealing with other fellow-Indians, unless they had worldly importance, were always peremptory. They seemed to be bursting with self-importance and awareness of their power, and were always standing on their dignity. I give one or two examples of what I saw.

One morning I was making a telephone call, and a very important Congressman (a member of the Working Committee), was sitting with a friend nearby. My contact at the other end was speaking in very fast Hindi which I had difficulty in following. So, I asked the important person if he would speak to the man and tell me what he was saying. Not even looking at me he said curtly that he would not. We Bengalis have a story to illustrate the difference between a man who is a gentleman and one who is not. It runs like this. One man asked another to do some little thing for him and got the reply: ‘Am I your servant?’ The other simply answered: ‘Oh no, only I thought you were a gentleman.’ Perhaps the Congress leader thought that I was ordering him as if he were my servant.

Another incident in which I was involved was more revealing, because it was created by a Congressman of a much lower rank. At the same time as the meetings of the Working Committee were being held upstairs, downstairs, in Sarat Bose’s library, the Speakers of the Legislative Assemblies and Councils of the provinces in which Congress was holding power, had their conference. They met to have a concerted policy of giving as much trouble to the British administration as possible without giving a blatant exhibition of partisanship in conducting the proceedings. The Speaker of the Madras Assembly was a dark, hairy, and obese Tamil Brahmin, who was a strict Gandhian. Even when attending such formal meetings, he would wear only a short loincloth reaching down to his knees, and for the rest would be barebodied.

One day at about lunch time he came out of the conference room and asked me to get a car to take him to the house where he was staying. I looked for Sarat Babu’s cars and found that they were out, and said apologetically: ‘I am sorry, all our cars are out.’ There were, of course, many more cars in the forecourt. He pointed to them and replied: ‘Ask any of the owners of those cars, and he would be proud to put his at the disposal of the Speaker of the Madras Assembly.’ I could not do that, but to put an end to my dilemma, Tulsi Goswami was coming out, and I asked him if he could lend his car. ‘Yes, of course,’ he replied, ‘but I’ll just go home and send it back. It would not take five minutes.’ He lived quite near. But the Speaker at once addressed Tulsi Babu directly: ‘I must have it first, my business is more urgent.’ Before Tulsi Babu could recover from his surprise, Kumar Debendralal Khan, son of the Raja of Narajol, said with his habitual politeness: ‘Tulsi Babu, you may go home. My car will take Mr. Speaker home. I am in no hurry. I will sit here and have more gossip.’ So, the Speaker went away in a much bigger car than Sarat Babu’s or Tulsi Babu’s.

The strong point of the elders of the Congress was their loquacity. They loved to talk, and felt that they were denied openings for their talents unless allowed to do so. Some members of the Working Committee talked for two hours about a question which could be decided in ten minutes.

Even then I had some realization that the personal leadership which the Congress was offering was not a decisive influence on the nationalist movement. Indeed, what these men did or said did not give shape to the nationalist movement. It ran on its own power, and its course was like that of a river flowing down to the sea, either cutting its way at some places or winding round the obstacles in the bends. What the leaders did was to ride on this current.

During the entire period of the Gandhian phase of the nationalist movement I heard people talking about the organizing capacity of the leaders. Even the British administration seemed to have been overawed by the notion. They did not understand the source of the effectiveness of the movement. They saw a whole people acting in unison, seemingly at the behest of the leaders, and never perceived that the behests came from the people, only to be put in words by the leaders. These men gave what might be called the passwords for the situations. All the supposed organizing capacity of the Congress was among the people, who acted uniformly all over India from the shared passion of the moment. Of Congress propaganda it might be said that it was exactly like the propaganda of the French Revolution. The leaders lived from hand to mouth both in respect of policy and action, until they could take advantage of the eruptions in the collective behaviour.

In the next instalment of this series, we will read some excerpts about the sort of women that populated the front ranks of this Gandhian Congress.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.