- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

Note: This essay is the final part of The Dharma Dispatch series documenting the methodical and systematic manner in which the British not only destroyed Indian food production but converted the country into a nation of beggars. This series has been excerpted from the meticulously researched book, “Annam Bahukurvita” authored by Dr. J K Bajaj and Dr. M D Srinivas with permission. Some formatting changes have been made.

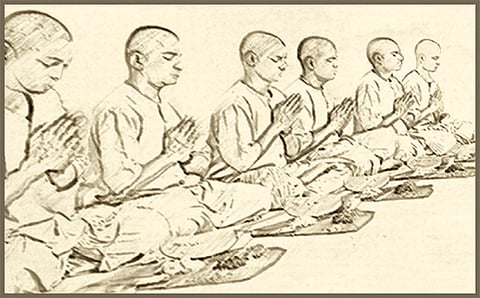

The Indian discipline of sharing was thus subjected, by the alien rulers and their Indian followers, to a concerted stream of ridicule, contempt and control that began with the coming of the British and did not abate till their departure. In time, the discipline began to weaken, and the will to flounder. But, it is not only the will to share food with others that came under stress during the British period, the capacity to share itself dwindled rapidly.

The abundance of food began to turn into a state of acute scarcity within decades of the onset of British rule. As the British began to dismantle the elaborate arrangements of the Indian society and began to extract unprecedented amounts of revenue from the produce of lands; vast areas began to fall out of cultivation and the productivity of lands began to decline precipitously. In the Chengalpattu region where the lands had yielded at least 2.5 tons of paddy per hectare on the average in the 1760’s, and where average yields according to the British administrative records had remained around that figure up to 1788 in spite of the devastating wars of the period, productivity had declined to a mere 630 kg per hectare by 1798.

Lionel Place, the British collector of the district at that time, was in fact greatly worried about the decline in productivity and the consequent difficulty of raising sufficiently large revenues from the land. He believed that part of the reason for the loss of productivity was to be found in the decrease in the availability of manure, resulting from a sharp decline in the number of sheep, which were being consumed in such large numbers by the Europeans as to “threaten an extermination of the breed”. He also felt that the proximity of the region to the fast expanding city of Madras was depriving the land of straw and dung. But perhaps the most important factor was that under the British dispensation, agriculture had become so un-remunerative that cultivators were loath to cultivate their lands; and Lionel Place often had to use force in order to make them take to the plough.

Thus Indian agriculture seems to have suffered a decline throughout the long period extending from late eighteenth century up to the time of independence in 1947.

The figures for availability of food in India clearly point towards widespread hunger of people and animals in India. And every available statistical indicator confirms the prevalence of hunger. Thus, according to generally accepted statistics, 40 percent of the Indian people do not have access to the bare minimum number of calories required for survival, 63 percent of children under the age of five are malnourished and 88 percent of pregnant women suffer from anemia.

But one does not need to look at figures to see the hunger that prevails. In every city and town of India one can see cows and dogs roaming the streets searching for bits of food amongst heaps of dirt. And, in the larger cities, one can see an occasional child or even an adult competing with the cows and dogs for a share of the edible waste. But nowadays there is hardly anything edible in the waste from Indian households; and the cows are often content with filling their bellies with mere paper and plastic, the dogs howl through the night in hunger, and the human children and adults stand and lie on the streets crazed by sheer starvation.

A journey through any part of India in the great railway trains, that crisscross the country heralding the arrival of modernity here, brings one in even closer contact with hunger and starvation. Young children, with their eyes glimmering with the sharp intellect of early age, sweep the floors of the trains to earn a bellyful, and fight with the passengers, with the waiters and with each other for the right to the left-overs of food. Their less adventurous and less energetic brothers wait on the platforms silently watching the passengers eat and almost cry with gratitude for the gift of a single slice of dry bread or a stale roti or idli.

The scenes of hunger and starvation become even grimmer as one heads towards the great pilgrimage centres of India, the roads to which, as we have seen, used to be dotted with chatrams where bells were rung at midnight to invite the laggard seeker to come and receive his food, and where orphaned children of the passers-by were provided shelter, food, education and care till they were ready to face the world on their own. The persisting image that the pilgrim centres and the trains leading to them now leave on the mind is that of immense hunger and starvation. One of the most unfortunate images that comes to mind is that of a child of five soothing a younger child of two with a rubber nipple at the end of an empty bottle of milk on the main street of the great city of Tirupati, where a vast stream of pilgrims converges every day.

The statistical figures and the day-to-day images on the streets all speak of a great hunger stalking the lands of India. But, we insist that we have sufficient food for ourselves. The economists and the policy planners have been claiming such sufficiency of food in India at least since the early seventies. They have now begun to claim that the food available in India is not only sufficient, it is a little too much for our needs, and we should make efforts to export some food and shift some of the food grain lands to more exportable cash-crops.

The claim of sufficiency is based on the fact that the food that we produce cannot all be sold within the country at economic prices. There is no dearth of food, it is said, for those who can afford to buy; and those who cannot buy probably do not deserve to be fed. Lack of food grains for the animals is explained through a similar argument: Those who feed good food to the animals, it is said, also eat their flesh; we do not rear animals for economic exploitation, so we do not need to allocate food grains for them. Thus we condone both the scarcity and the hunger.

But, the essence of the Indian position on food, and perhaps the position of all societies on the question of food, is that all those who are born deserve to eat. Others would perhaps expect some economic returns from the feeding, Indians believe that feeding is its own reward. But perhaps no society in the world believes that people or animals can be left to starve if they cannot be put to use. Healthy animals and healthy men are useful in themselves.

We, who as a people, used to be so scrupulous about caring for all creation, have become callous about the hunger and starvation of people and animals. We know of the hunger around us, and we fail to care. We, all of us together, all the resourceful people of India, bear this terrible sin in common.

But we cannot continue to live in sin. No nation with such a sin on its head can possibly come into itself without first expiating it. We should begin to pay attention to the lands and to the fulfilling of the inviolable discipline of annam bahu kurvita. But we cannot continue to be indifferent to the hunger around us until the abundance arrives. Because, as classical India has taught with such insistence, hungry men and animals exhaust all virtue of a people. Such a nation is forsaken by the devas, and no great effort can possibly be undertaken by a nation that has been so forsaken. In fact, not only the nation in the abstract, but every individual grhastha bears the sin of hunger around him. We have been instructed, in the authoritative injunctions of the Vedas, that anyone who eats without sharing, eats in sin, kevalagho bhavati kevaladi.

Therefore, even before we begin to undertake the great task of bringing the abundance back to the Indian lands, we have to bring ourselves back to the inviolable discipline of sharing. We have to make a national resolve to care for the hunger of our people and animals. There is not enough food in the country to fully assuage the hunger of all; but, even in times of great scarcity, a virtuous grhastha and a disciplined nation would share the little they have with the hungry. We have to begin such sharing immediately, if the task of achieving an abundance is to succeed.

To us, Indians, sharing of food comes naturally. We do not have to be taught how to share, how to perform annadana. Because, we have been taught the greatness of anna and annadana by our ancestors, and we have practiced the discipline of growing and sharing in abundance for ages. For such a nation to obliterate the memory of a mere two centuries of scarcity and error is a simple matter. Let us recall the inviolable discipline of sharing that defines the essence of being Indian. Let a great annadana begin again through the whole of this sanctified land. Let a stream of anna begin to flow through every locality of the country. The abundance will surely arrive in the wake of such annadana.

May we have the strength of mind and body to be Indians again, and fulfil the vrata of growing and sharing a plenty.

Concluded

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.