- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

One of the glorious parts of the Arthasastra is section dealing with the education of princes. A prince who undergoes this rigorous education becomes a king fit to rule the “whole earth.”

We notice the practical application of this Kautilyan foundation in almost all our great Hindu emperors. The historical accounts of how these emperors were educated, their daily routine, and their command over an astonishing range of subjects are thrilling and inspirational. Without exception, all great Hindu monarchs were primarily, extraordinary warriors, well-versed in wielding a number of dangerous weapons and masters in hand-to-hand combat. Sri Krishnadevaraya would wake up early in the morning, apply oil all over his body and perform vigorous exercises for about two or three hours. He was also a powerful and distinguished wrestler and became one of the greatest royal patrons of this art. And then, his linguistic and literary accomplishments are best reflected in his epic Amuktamalyada. The very fact of that the Vijayanagara Empire attained its loftiest peak of economic prosperity during his reign is itself a huge testimony to his grasp of economics. This list can be expanded with any number of such accomplishments in other spheres.

Broadly speaking, the extraordinary legacy of Chanakya and his work is its inherent capacity to produce powerful conquerors, emperors and administrators from the scratch. Indeed, Kautilya himself cemented this royal path by taking a boy of humble origins and transforming him into Chandragupta Maurya, Bharatavarsha’s first national monarch.

This capacity for creating emperors originates in the theory and practice of the ancient Sanatana ideal of a Chakravartin. In turn, the Vedic conception of the Ashwamedha Yajna inspired and fueled the real-life attainment of this powerful title and throne.

Like his predecessors, Kautilya too, regarded Bharatavarsha as a Chakravarti-Kshetra, i.e., the land spreading towards the Himalaya from the southern sea.

The importance of this ideal cannot be underestimated because of the central role it played throughout the Hindu civilizational history. All our great kings took it seriously, akin to a Raja-Mantra. We must remember that every Hindu king who embarked on a political career ultimately aspired to become a Chakravarti. The extent of the king’s final success in this endeavor is immaterial here.

But the list of Hindu emperors who did attain this exalted status and title of Chakravartin is truly impressive. Spread over 2500 years, this is the (partial) list: Chandragupta Maurya, Ashoka, Pushyamitra Sunga, Bhavanaga, Pravarasena, Chandragupta I, Samudragupta, Chandragupta Vikramaditya, Harshavardhana, Pulikeshi II, Amoghavarsha, Krishna III, Rajaraja Chola, Rajendra Chola, Sri Krishnadevaraya, Shivaji, and Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

When we think about it for a moment, we understand the real impact of Chanakya. He is indeed the unrivalled, inspirational, and later, the invisible Director of grand Hindu Empires—director in the sense that his Arthasastra is a detailed manual of military strategy, administration, national security and economic prosperity.

On the other side, Kautilya’s rules for dealing with bad and errant princes, ambitious relatives and scheming vassals are also reflected in our political history.

The Chalukya emperor Pulikeshi II first defeated his rebellious younger brother, Kubja Vishnuvardhana, pardoned him and sent him to rule distant Vengi (near Warangal).

Most Vijayanagara rulers made their family members and close relatives as governors and viceroys of distant provinces to keep them away from palace conspiracies and attempted coups. In spite of such stringent measures, they were not always successful. The subordinate ruler, Saluva Nrsimharaya I managed to usurp the throne from the previous dynasty to which he had sworn loyalty.

Perhaps an overlooked part of the Kautilyan political tenet is the manner in which it places restraints and checks and balances on the king by stressing on Dharma. Even here, Kautilya adhered to the wisdom of his predecessors. Thus, a Hindu king could never become an unchecked despot like a Sultan or a medieval Christian king for precisely this reason. As we never tire of repeating, the fundamental difference between Sanatana and non-Sanatana statecraft is Dharma.

This profound principle had a lasting impact not only on kings but even village heads. For example, if a king had imposed a heavy tax and people complained, he would give them a remission. Which also reveals the historical truth that even the ordinary citizen could make direct appeals to the king.

We have hundreds of such examples in Hindu history.

In the reign of the Vijayanagara king, Devaraya I, tax remission was granted to all the weavers in Chandragiri when the governor found that excess tax was being collected so far.

Similarly, in 1473, in the Gandikota Province, all the Kurubaru or shepherds were completely exempted from the tax they were paying so far.

In 1086, Kulothunga Chola I conducted an extensive land survey throughout his kingdom, and after reading the findings, he ordered the remission of all customs duties. This singular act had a profound impact on his citizens. These overjoyed masses gave him the title, Sungadavirta Chola: “the Chola who exempted Sunkas (tax).” At the heart of such munificence was the desire of the king to be seen as an upholder of Dharma and as a Praja-Vatsala: affectionate to the citizens.

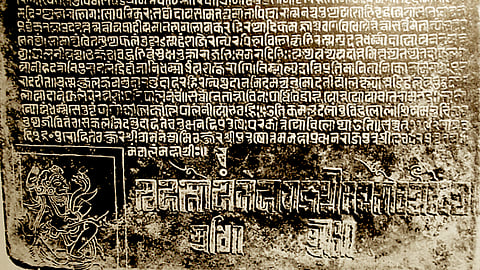

Another important area of Hindu civilizational history where we notice Chanakya’s pronounced influence is his elaborate and fine section on drawing up Shasanas or inscriptions. Kautilya stresses on elegant handwriting, linguistic eloquence, clarity, and etiquette.

In fact, writing Shasanas eventually evolved into a separate art form and became a highly lucrative profession. The better part of Hindu history reveals an array of truly celebrated Shasana-writers, and several Shasana-poems can be regarded as brilliant literary feats. Some of these Shasana-writers enjoyed celebrity status rivalling that of the braindead film and fashion celebrities of our time enjoy.

Ravikeerti, for example, was one such celebrity Shasana-writer who gives us impressive details of the early Chalukyan period. In fact, Ravikeerti’s inscriptions still form the primary source for understanding Chalukya history. Next, we have the celebrated Old-Kannada (Halagannada) poet Ranna—whose family profession was a bangle-making and selling—who began his initial career as a Shasana-writer.

Then we have a remarkable 15th century inscription found in the Anantapur district. This Shasana gives an elaborate tutorial on how to write the perfect Shasana-padya (poem).

There is also a delightful Daana-Shasasana (donation grant) belonging to the Vijayanagara period which praises the donor, the Shasana-writer and the Shasana-engraver as follows:

May prosperity accrue to the writer and engraver of this Shasana and may the auspicious Sri Venkateshwara Swami of Tirumala bless their entire lineage.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.