- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

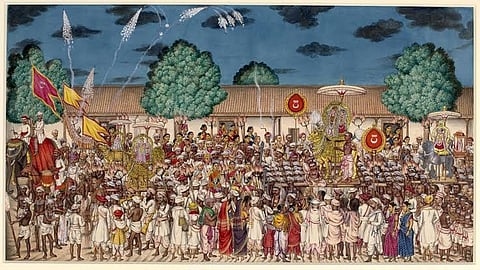

THE DEFINING, DISTINCTIVE AND CARDINAL FEATURE of life in ancient India from the Vedic era was the foundational spirit of honest cooperation and harmony. This reflected itself in all areas: religion, society, politics and economics.

Perhaps the best illustration of this spirit is just one word: Yajna. Today, we associate Yajna almost exclusively with a religious ceremony or what is wrongly known as ritual. But as long as India retained her original character, Yajna was a profound activity of national sharing…in fact, the correct meaning of Yajna is “sharing,” and not “sacrifice.” In a sense, Yajna was an institution which provided a spiritual basis for national cooperation. It is in Yajna that we see the practical manifestations of profound conceptions such as Rta, Rna, Dharma, etc. It was also a significant engine of economics but that is a topic for another day.

The spirit of cooperation is primarily a social instinct rooted in basic human impulses. Spirit acquires meaning only through activity. And so, the aforementioned cooperative spirit derives meaning and will function in the real world only through conscious social organization.

Further, this organization—its form, nature, structure, and practical operation also depends on the circumstances that births it and in which it operates. But while the nature of these circumstances dictates its form, functioning, etc., the character of its evolution and development depends to a great degree on the unique genius of the society and culture in which it is incubated and fostered.

This genius is precisely what we observe in the corporate and business life of ancient India. In the real world, this life revealed itself in the following organizations, which continue to exert an enduring influence on our contemporary life as well. Here is a partial list:

Jati (not caste)

Sangha

Shreni

Puga (can be likened to today’s Association of Persons, a cooperative society, and so on).

Gana

ON A FUNDAMENTAL PLANE, a study of business and corporate life in ancient India will open up a whole new world, to put it mildly. It will reveal itself to us a stunning array of the real perspectives, attitudes and impulses of life that animated our people so far back in time. More importantly, this study of business life in ancient India shows us the innate spirit of nobility and refinement that informed and permeated all other areas of our national and social life.

What has been unfairly propagandized as the “caste system” was actually two things at the same time: one, it was a social corporation much like today’s FICCI and similar bodies; and two, it was also an economic unit taken as a whole.

Corporate organizations in ancient India have interesting roots. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad for example, is an early reference. It says that just as how society was divided into four Varnas, the Devatas also had four Varnas.

The story which follows is pretty thrilling.

Brahma was not content with creating only the Brahmanas and Kshatriyas because these two Varnas did not know how to create and acquire wealth. And so, he created the Vaishya known by the term Gana-shah. In fact, the meaning of this word is highly interesting in itself. It basically implies that it is only through cooperation and not by individual effort that wealth is acquired.

This evidently shows the fact that there was thriving corporate activity in India’s economic life as early as the Vedic period. Indeed, for countless centuries, the business community throughout India had organized itself into Ganas.

But on a very mundane plane, this cooperation or organization of business community into Ganas was also practical necessity as we shall see.

Now we can quickly look at only some of the major forms of corporate organizations in ancient India:

Gana: It was an overarching and a highly fluid organization which generally means an association of traders and merchants…on in general, any corporate body in the current sense of the term.

Pani: similar to Gana. It is derived from the root, Pann: to barter; to negotiate. Over time, it acquired other meanings such as a miser, a path, a market, and so on.

Puga: Corporations living by the profession of arms. Or entities which supplied soldiers for hire. This genre of corporations also had a clear leadership hierarchy. We can think of them as corporations of warriors and they were in continual existence for several millennia.

Samavaya: in general, an assembly or congregation of people meant to discuss or carry on some kind of commercial activity.

ONE OF THE MOST ENDURING and ubiquitous corporate organizations was something known as the Shreni, and it merits some detailed examination. But before that, we can cite an interesting titbit. The head or chief of a Shreni was the Shreshti. This is the origin of the ubiquitous surname, Seth.

In general, a Shreni was a guild or commercial body in ancient India. We can think of it as follows: practically, all different branches of occupations, professions, and trades had a well-defined organization of some sort. Each such organization or corporate had the authority to lay down rules, laws and regulations for its members, and these were recognized as valid in the eye of the law. The representatives of a Shreni had a right to be consulted by the Government authorities including the King himself in any matter that concerned it.

A highly interesting facet of Shrenis is the fact that while its legal character was a guild or corporation — I will use the terms guild and corporation interchangeably—its members belonged to the same or different Varnas and Jatis. But all of them followed the same trade or industry.

Thus, nearly all branches of professions, industry, trade, etc., formed their own guilds but their numbers varied over different periods and geographical locations throughout our history. However, the most common or standardised number of guilds starting from the Buddhist period onwards is eighteen. In some cases, there were as many as thirty-two. But overall, the number of guilds or corporations in the long history of India is rather substantial, which only shows how pervasive and complex the system of our corporations was. Here is a partial list of such guilds or corporations:

Guilds of wood-workers including carpenters, cabinet-makers, wheel-wrights, builders of houses, builders of ships and builders of vehicles of all sorts.

Workers in metal, including gold and silver.

Stone workers

Leather workers

Ivory workers

Workers fabricating hydraulic engines (Odayantrika).

Bamboo workers

Braziers or brass workers

Jewellers

Weavers

Potters

Oil millers (Tilapishaka)

Basket makers

Dyers

Painters

Corn-dealers

Cultivators

Fishermen

Butchers

Barbers and Shampooers

Garland makers and flower-sellers (Malakara)

Mariners

Herdsmen

Traders, including caravans and merchants

Robbers and freebooters

Militia who guarded caravans

Moneylenders

These professional guilds also formed part of the local political assemblies.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.