- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

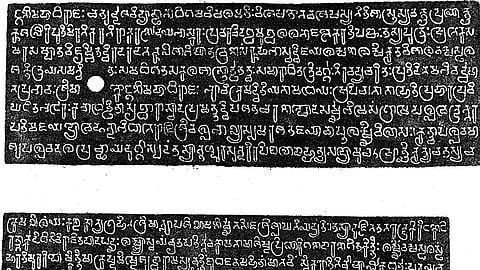

EVEN ON THE MUNDANE PLANE of information and data gathering, we have no other recourse than epigraphy to accurately reconstruct the history of Bharatavarsha. While literature and travelogues are valuable sources, they do not possess the unimpeachable authority of inscriptions for a straightforward reason as we shall see.

The Indian word for inscription or charter or grant is Śāsana, which generally means, “decree,” “legislation,” “fiat,” “order,” “statute,” or “law.” In a general sense, Śāsana means “rule” or “regime,” in the sense of “Government.” In other senses, it also means “grant,” “endowment,” “deed” and so on.

The wording at the beginning of a royal Śāsana was typically written in this manner: “All of you [i.e., citizens] listen! On this date and at this place, it has been proclaimed by His Majesty that this order must be followed by the people,” followed by the full text of the order. It would be signed off by the king, the relevant official and sealed with the royal seal and emblem. This is entirely consonant with an ancient dictum recorded by the Smritis: that any king who did not pronounce an order or issue a charter in the written form was not a king but a thief. It was also held that an official who carried out administration without the king’s written order to the effect was also a thief.

Thus, Indian inscriptions are actually Government records. This is true whether the monarch himself issues them or his officials or private persons issue them, subject to kingly sanction. To draw a contemporary analogy, an endowment or CSR funding given by a private company to a temple or university is legally and judicially valid even though it does not directly originate from the Government.

Therefore, Indian inscriptions provide us authentic — and in most cases, detailed — information about a king or his lineage and the historical events that they record. These details are often minute and elaborate down to the last "T."

While literary and other works provide information about kings (for example, Bana’s Harshacharita) and some historical events, they often occur in an incidental or ancillary fashion. Moreover, depending on the litterateur’s own proclivities and biases, the accuracy of the historical element in his work becomes questionable. However, the information in inscriptions is unambiguous, complete with details of date, time, Muhurtam, place, etc., as listed earlier. For example, inscriptions were written by poets or writers who had absolute command over the information about a royal lineage including intimate details of present and past kings and their extended families. After the first draft was completed, it was shown to the king and his cabinet and upon approval, it was inscribed on copper plates or stone or other material. The names of the inscription writer and the engraver was also recorded. Copies of these inscriptions were preserved in the royal archives for reference by successive kings. If an old inscription was damaged or broken, fresh copies were made.

Hindu Inscriptions fall into the following broad categories:

Royal orders and charters related to various administrative matters.

Grants and gifts and endowments issued by the monarch or his officials or private institutions and individuals. These are the generally known as Dāna-śāsanas, which constitute the bulk of the Indian epigraphical repository.

Praśasti or laudatory inscriptions celebrating a king or chieftain’s prowess, military victories, his generosity and other virtues.

Heroic tombstones commemorating the glory, nobility and valour of ordinary persons who have died after performing extraordinary deeds. In Kannada, these generally fall into two categories: Māstikallu (derived from Mahāsati, meaning virtuous or great wife) and Vīragallu (tombstone of a warrior). A subcategory is the Nisidi, largely reserved for extolling Jaina ascetics.

Charters describing an administrative set up — the famous Uttaramerur and Ukkal inscriptions fall in this bracket.

Miscellaneous inscriptions recording a wide ambit of social, economic, religious and philanthropic activities such as building public lakes, wells, parks, dedicated flower-gardens (Nandanavana), travellers’ rest houses, temples, commissioning caves for mendicants and monks, raising funding for a guild, tax exemption for specific charitable purposes, endowing agrahāras and Ghaṭikas (educational centres), donating cows, and oil for temple-lamps… the list is almost inexhaustible.

Three significant points must also be mentioned in this context.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.