- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

ACHARYA JADUNATH SARKAR has commandeered a lasting maxim as far as the military geography of Bharatavarsha is concerned:

Because the maxim is so straightforward and commonsensical, its centrality in deciding the fortunes of Bharatavarsha at critical junctures in our history has been overlooked for the most part. Geography is also war because terrain dictates both strategy and tactics. Intertwined with terrain is climate. Together, they author and alter history, and nowhere is this more pronounced than in India.

And so, we humbly echo the profound question the Acharya asked himself more than sixty years ago: What is the practical use of the study of the history of military geography to a soldier of today? Is it an unprofitable act of pedantry? And he answers:

No; for if it were so, an intensely practical nation like the English would not have found chairs of military history nor made the military historian a necessary member of a Staff College. The Navy is the senior service in Great Britain, and the importance of military history in its proper functioning is clearly set forth in discussing the life of Sir Herbert Richmond, an experienced admiral and erudite scholar, who may well be called “the Mahan of England.” … History [is] not an end in itself, but as a means of learning something about strategy… Seeing clearly the need to evolve a doctrine of war if the Navy’s effort was not to be wasted when the test came, Richmond was an enthusiastic advocate of the creation of a Naval Staff. (This was done by Mr. Churchill in 1912 and Richmond was appointed to it as Assistant Director of Operations next year. The World War came on 4th August, 1914).

Jadunath Sarkar had correctly hit the spot. Sometime in mid-19th century, Lord Canning proudly boasted that India would firmly remain under England’s stranglehold as long as “our Naval superiority in both Europe and the Indian Seas remained intact.” In fact, there is a crying to study the manner in which the centuries-old Indian naval prowess was criminally squandered away by the Mughals to the great delight of European powers. The indomitable naval Kshatra built up and fortified and sustained by the Gupta and the Chola had sunk into the decadence unleashed by Muslim rule. Thus, even as early as Jahangir’s rule, substantial maritime areas in and around the Bengal region were under the control of the Dutch, Portuguese and later, the British.

But to summarise a long story, the patriot and nationalist in Sarkar offers a precise but humble explanation for the aforementioned study:

This is a civilian’s sufficient apologia for venturing into this field. There is a practical necessity why the wars of India in the past ages should be studied by the soldiers and sailors who are to defend the free India today.

It must be remembered that the Acharya wrote this about fifteen years after India attained political independence and was dangerously perched on the branch of a skirmish with China.

TO THE INHERITED HINDU CIVILISATIONAL consciousness, the sacred geography of Bharatavarsha is broadly divided into two parts: Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha. A geography unified by a shared spiritual culture where political boundaries were secondary at best.

In general, Uttarapatha signifies the entire region north of the Vindhya Range, which included the whole of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Dakshinapatha was the whole region lying south of the Vindhyas. The topographical layout of Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha are distinguished more by dissimilarity than resemblance.

Three features in the geography of Uttarapatha stand out in a pronounced fashion.

The first is the non-contiguous, federated network of awesome snow-clad mountain ranges crowned by the familiar natural fortress of the Himalayan Range, the guardian of northern India since the dawn of its civilisation. The Sulaiman Range closes the Himalayan bracket on the northwestern frontier sloping down to the mouth of the Sindhu River, which empties out into the Arabian Sea.

Running roughly parallel to this range and situated well within India is the dwarfish Aravali Range that overlooks Delhi at its northern end. A freefall from the Aravali Range lands the fortunate soul atop one of the peaks of the mighty Vindhyan Range, the scarped blanket that covers Central India from west to east and divides the Indian peninsula. Vindhya. The natural separator of Bharatavarsha into Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha. Its southwestern tip, separated by the fertile and gorgeous Narmada Valley, is where the Satpura Range begins and ascends and expands eastwards into an enchanting lushness, until it is rudely cut off at the Baghelkhand Plateau.

The second feature is the collection of hostile playgrounds of nature strewn with deserts, plateaus and interminable stretches of hard, bare rocks and scorching treeless terrains, all of which fall under the suzerainty of these mountain ranges. The Marusthali or the Thar Desert directly parallel to the Aravali Range, and the barren Rann of Kutch to its southwest have sustained their fame of being inhospitable. The Madhya Bharat Pathar (Plateau) situated at the western opposite of the Vindhya Range is a rugged terrain dotted by boulders and scarps and threatening ravines.

The third and the most important feature in the geography of Uttarapatha is where the cradle of the Sanatana Civilisation birthed itself, to borrow a philosophical maxim from Vedanta. Our culture and civilisation began as the refined fruits of eons of spiritual contemplation carried on in the quiet and undisturbed caves and crevices of the Himalayan Range.

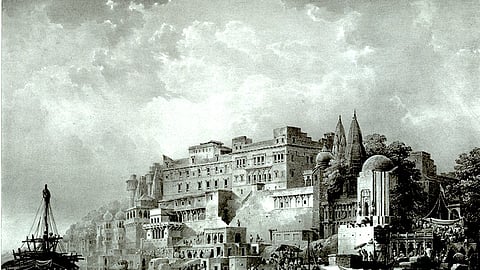

From a contemporary perspective, this is the vast arc and a magnificent geographical umbrella that shelters and nurtures a 3300-kilometre expanse from Calcutta in the East to Karachi in the West. The journey which begins at Calcutta first slopes upwards, reaches Patna, moves west, touches Varanasi and then Prayaga, and travels further northwest passing through Agra and then hits Delhi and from there, climbs upwards to the northwest and culminates at Lahore. From Lahore, it slopes downwards to reach Multan before ending its journey in Karachi. Acharya Jadunath Sarkar describes this entire terrain in his characteristic fashion:

From Calcutta to Lahore the distance is 1,300 miles and yet the difference in height above sea-level between these two cities is only a thousand feet, or in other words the ground rises only nine inches in one mile of road… This would not be surprising in the Bengal Delta, but a thousand miles upcountry from Calcutta, the ground formation is the same in the Delhi district. The river Jamuna enters the district at a height of some 710 feet (at the north end) and leaves it at about 630 feet above sea level, with a course within the Delhi limits of rather over 90 miles and the average fall of between ten and eleven inches to the mile.

This is the Great Indian Fertile Plain, home to the maximum number of sites venerated by the Hindu civilisational memory. It includes the hallowed Aryavarta, it was home to the largely forgotten but glorious Sindhu-Sauvira Desha, it is the Ganga-Kshetra (generally but incorrectly known as the Indo-Gangetic Plain) and is the pocket of the celebrated Pancha-Nada Kshetra (undivided Punjab). To an appreciable extent, the entire region retains its preeminence as one of the most ancient civilisational locales in human history.

Indeed, the near-precise recognition of the boundaries of Aryavarta is an eternal testimony to the prestige and farsighted genius of our ancient seers and Rishis who recognised this geography and bequeathed its knowledge to hundreds of generations in an era characterised by an absence of modern transport technology.

The southern limit of Aryavarta (or more broadly, the Uttarapatha) is the Vindhyan range. The Vindhya (literally meaning “to obstruct”), like its more imposing and majestic brother-rival Himalaya, has a paramount salience in the annals of Hindu sacred literature. Vindhya is also known as Vindhyachala, where achala means mountain. The Mahabharata calls it the Vindhyaparvata. The Kaushitaki Upanishad calls it the Dakshinaparvata. Ptolemy, the Greek geographer called it Vindius or Ouindion.

Like Himalaya, Vindhya too, is a stern but highly accommodative mountainous monarch who places his lofty pedestal obediently at the feet of Devatas and Rishis. If Himalaya gave his daughter Parvati—daughter of Parvata or mountain—in marriage to Shiva, Vindhya agreed to dwarf his growth at the command of the Rishi Agastya.

The “modern Hindu” mind unthinkingly discards an ocean of values embedded in such stories based on undefined notions of “realism.” One such value—on the “practical” and “realistic” plane—is the fact that for more than a millennium, these tales constituted an entire education that taught the nuances of our geography down to the last unlettered man without the boredom induced by modern “geography lessons.” And our people gladly learnt it without formal education. The medium was the story. The language was sanctity. Indeed, the reverence ascribed to our geography was what preserved their beauty and prevented their destruction and transmitted our literature and culture.

While the Great Plain of North India is continuously hydrated by a complex web of rivers, the huge region to the south of the Vindhya is walled by a chain of intimidating mountain ranges and harsh passes and treacherous ravines and arid plateaus and deceptive rivers.

This broad layout of Dakshinapatha (or simply, Dakshina), the original word for “Deccan” has a continuously recorded history dating back to the third century BCE. Muslim chronicles pronounce it as Dakhin and Dakkhan. ”Deccan” is the anglicised form of this Islamic linguistic corruption.

In turn, the Deccan is further cut up into three major slices:

The Northern Deccan Plateau comprising the Maharashtra Plateau, located south of the Satpura Range.

The Eastern Plateau that includes Telangana and Rayalaseema running parallel to the East Coast.

The Southern Plateau comprising the northwestern regions of Karnataka, sandwiched between the Northern and the Eastern Plateaus.

And then, the elongated natural fortress of the Western Ghats lying parallel to the Arabian Sea safeguards the entire plateaued region of Maharashtra and Karnataka while the Eastern Ghats running parallel to the East Coast affords a similar protection to the Telangana Plateau.

This complex geography is further complicated when we survey its zigzagged riverine networks. All three major rivers, Godavari, Krishna and Kaveri originate as streams in the Western Ghats and as they stretch and sprawl like a new bride, they collect rain from the bordering hills before branching out into scores of diverse-sized tributaries and finally emptying into the Bay of Bengal. From one perspective, the civilisational history of Dakshinapatha is the history of its riverine cities. Likewise, the mercantile routes that led to and continued in South India from time immemorial followed the course of its rivers.

From a historical perspective, Dr. Jadunath Sarkar again paints a captivating panorama of Dakshinapatha:

Thus Nature has cut the Deccan up into many small isolated compartments, each with poor resources and difficulty of communication with its neighbours… long parallel mountain chains… run west to east, cutting the country up into isolated districts…

This overall picture of Bharatavarsha’s geography comes alive in a brilliant and often brutal fashion when we regard it as a Great Military Theatre placed on the canvas of Time. In a limited sense, in some of its particulars, it has all the dimensions of a Cosmic Play that Bharatavarsha was both fortunate and ill-fated to participate in.

We will explore this theme in the next episode of this series.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.