- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

It is an extraordinary testimony to the gritty endurance of the Hindu Shahi Kings of northwestern India who were left orphaned after the decimation of the powerful empire of Kanauj but still successfully commanded a vast region that included the Kabul Valley, Gandhara, Laghman, Kashmir, Sirhind, and Peshawar, which was central to their dominions. In many ways, the condition of the Hindu Shahis of that period resembles that of modern-day Israel: surrounded on all sides by bloodthirsty religious imperialists just waiting for that one chance, one fatal slip. What kept them at bay were the expensive, horrific tales of the “terrible Hindu valour at the battlefield,” which they dared not verify personally. Indeed, it was precisely this fabled Hindu valour that made major and minor Muslim chieftains in the general region of Khorasan and Transoxiana seek the safety of an alliance with these Hindu Shahis against their more barbaric Central Asian rivals.

However, without the all-encompassing civilisational vision of say, a Chakravartin or Samrat, these Hindu Shahi Kingdoms underwent cyclical political turbulences all of which led to their destined downfall.

Our story approximately begins roughly at the end of the ninth century.

In 870 CE, Yaqub bin Layth, a Turkish coppersmith, mercenary, and adventurer from Seistan who began his career as the chief of a band of brigands, quickly attracted the attention of the Abbasid Caliphate for his successful exploits against their sworn enemies, the Kharijites who had dared to rebel against the authority of the Caliphate. Layth rose through the ranks meteorically and became the founder of what came to be known as the (short-lived) Saffarid Dynasty. With an eye on Al-Hind, he sent a honeyed message to the ruler of Kabul and literally stabbed him the back with a lance when the two met. His Turkish army then invaded the Hindu kingdoms of Kabul and Zabul. The fate of Zabul was particularly gruesome: after its king was killed in the battle, its entire population was converted to Islam by force. However, this bloodbath was still a mere eclipse that had engulfed Kabul.

After the death of Yaqub Layth, the Hindu king Lalliya Shahi (or Kallar) who had shifted his capital to Udbhandapura returned and quickly reconquered Kabul. However, by then, Kabul had permanently lost its original Hindu character. The Arab traveler-geographer-chronicler Istakhri gives the following picture of Kabul in 921 CE.

There was a lull of sorts for the next forty odd years. In 963 CE, with Ghazna (or Ghazni) in Eastern-Central Afghanistan as his base, Alp-Tigin , a Turkish slave commander of the Samanid dynasty succeeded in establishing an independent Muslim principality in Kabul. However, originally, it was his daring capture of Ghazni that truly changed the fortunes of mainland India for the worse.

Ghazni, meaning “jewel,” remains a highly strategic city located on a plateau and for thousands of years served as the main road connecting Kabul and southern Afghanistan, sandwiched between Kandhahar (or Gandhara) and Kabul. It was originally founded as a small market town and is perhaps one of the few antiquarian cities which had the misfortune of being kicked around like a football: from the Achaemenid king Cyrus II to Alexander to the Saffarids to the Ghaznavids to the Ghoris to the Mughals to Nadir Shah to the Durranis to the British and finally, to the Taliban. Perhaps no other ancient city has been repeatedly destroyed so spectacularly at sickening regularity. Till this day, Ghazni retains its preeminence as the key to the possession of Kabul.

Which is why Alp-Tigin’s capture of Ghazni received formal recognition from the Samanids. He was now the official governor of Ghazni, a title that would eventually pave the way for sweeping, barbaric and history-altering changes.

However, Alp-Tigin didn’t live long to savour the fruits of his conquest. He died just a few months later, in September 963 CE. His slave, son-in-law, and general, “beloved prince,” Abu Mansur Sabuktigin succeeded him in 977 CE after a period marked by weak successors and the misrule of Pirai, another slave of Alp-Tigin. Pirai was expelled from the governorship and Sabuktigin took his place in 977 CE. However, that was the beginning of his troubles.

To their everlasting credit, the Hindu Shahi kings in the Kabul Valley were not only alert to these rapid and far-reaching changes but saw the perfect opportunity to do two things: to recover their lost territories and permanently seal the frontiers of India against further Mleccha incursions.

This heroic initiative was led from the front by the selfsame Parama Bhattaraka Maharajadhiraja Sri Jayapaladeva, the King of Udbhandapura. His first task was to prevent Sabuktigin from occupying Kabul. Jayapaladeva proactively went to work, first recruiting the disgraced Abu Ali Lawik, the last ruler of Zabul who had been so rudely ejected from Ghazni by Alp-Tigin. Then Jayapaladeva assembled a massive confederacy of troops from such diverse regions as Delhi, Ajmer, Kalinjar and Kanauj and attacked Sabuktigin in 986-7 right in Ghazni. The pitched battle lasted several days and casualties were high on both sides. Then, weather played spoilsport and Jayapaladeva was forced to negotiate for peace. However, it wasn’t an offer of surrender. In the letter to Sabuktigin, he thundered:

And to reinforce this, he sent ambassadors with variations of the same message:

Sabuktigin accepted the peace offer, which was short-lived. Eventually, hostilities resumed and Jayapaladeva and his Hindu army was defeated and driven out of Kabul. The control of the entire region including the Kabul Valley and the Sindhu River passed into Muslim hands.

However, Jayapaladeva did not give up.

Elsewhere in mainland India, in 974 CE, the Rashtrakuta Empire had sputtered to death at the hands of its feudatory, the Chalukya King Taila II (or Tailapa II). In its wake, a long and bitter war broke out between Taila II and Paramara Munja, the ruler of Malwa. Munja was ultimately captured and killed sometime between 995-7 CE. Taila II lived for barely a year after that.

In precisely the same year, Sabuktigin died and Abu-l-Qasim Mahmud, his elder son, revolted against his younger brother Ismail who had been appointed as Sabuktigin’s successor. After a long drawn battle , Mahmud broke open Ismail’s ranks, captured him and threw him in prison in 998 CE.

And then, Mahmud of Ghazni turned his attention to India.

Jayapaladeva was among the first of his targets. As a teenager, Mahmud had fought against the ferocious armies of Jayapaladeva as a commander under his father, Sabuktigin. That experience would now prove valuable because among other things, he had learnt an important secret about the Hindus. In that battle, he had found that Hindu soldiers would recoil in disgust when foul and vile tactics were used on the battlefield. For example, the use of feces mixed in water and splashed liberally on the fighting Hindu warriors yielded a rich military harvest.

Now as the unchallenged monarch at Ghazni, Mahmud would put all this knowledge to good use. This time, the theatre was at Purushapura or Peshawar, a mixed stage of ambition, retribution, fanaticism, destiny, and shortsightedness. As a seasoned military strategist, Mahmud did not underestimate the tenacity, will, grit, and fighting power of his old harasser, Jayapaladeva who was still around and in no mood to submit. Quite the contrary. He was determined to wipe out the alien Mlecchas from the region for good.

The sort of preparation that Mahmud made prior to attacking Jayapaladeva in itself is a superb proof to the kind of fear he had induced in the Mleccha. Jayapaladeva, by all accounts, a minor ruler compared to the other superpowers in mainland India. A superb proof and a timeless tragedy.

Mahmud’s prestige and authority bestowed by the Caliphate’s recognition enabled him to command arms and armies at will. His vassals and subordinates and chieftains agreed to furnish 1,00,000 men whenever he wished. Then he convened a war council in which he declared that he sought Allah’s blessings to “raise the standard of Islam,” of widening its dominions in Hind and to bring the full light and the strength of justice of the Only True Faith in this land of darkness and injustice and infidelity. Writing in hindsight, the medieval Muslim chronicler, Abu'l-Husain Utbi is certainly convinced that Mahmud was indeed guided by the light of Allah who also bestowed dignity and gave him superb victories in Hind.

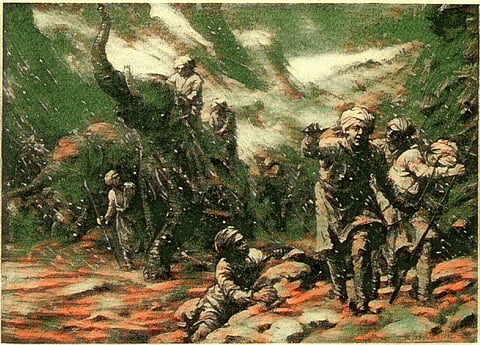

Mahmud pitched his tent outside the city of Jayapaladeva, “the enemy of Allah.” However, as we have seen, Jayapaladeva had already been proactive. This “villainous infidel” launched the offensive with a solid troop strength comprising 12,000 horsemen, 30,000 foot soldiers, and 300 elephants which met Mahmud’s 15,000 strong cavalry and a few hundred foot soldiers. However, weather played spoilsport once again, “amid the blackness of clouds.” Jayapaladeva decided to withdraw strategically. Besides he had had previous experience of a battle with these Mlecchas—with a much younger Mahmud. He used the strategic withdrawal to buy time, to wait for more reinforcements and avoided direct conflict for days. However, banking on a shrewd and daring gamble, Mahmud attacked Jayapaladeva first, taking him by surprise. Confusion was the first response from Jayapala’s unprepared army led by the elephant force which formed the mainstay of his force. His soldiers suddenly jolted by this unexpected assault, began shooting arrows wildly, randomly, killing and wounding fellow soldiers. The military defence quickly turned to a chaotic melee. Disorder replaced discipline. The battle lasted just a few hours at the end of which Utbi gloats how the

Characteristically, Utbi the chronicler attributes Mahmud’s victory to the ignorance of the idol-worshipping infidels about the word of the Only True God. He quotes the Quran in support of his claim:

Oftentimes a small army overcomes a large one by the order of God.

Like Muhammed bin Qasim, but only with greater savagery, Mahmud of Ghazni gave “the enemy of God,” Jayapaladeva, the firsthand experience of being a prisoner of an Islamic war. His children, grandchildren, relatives, nephews, generals, and the “chief men of his tribe” were bound with ropes and

And like Qasim, Mahmud next plundered Jayapala’s dominion, stripping everyone including non-combatant citizens of pearls, shining gems, rubies, and gold. The additional booty he pillaged included the thousands of slaves, “beautiful men and women.” Returning to his camp, Mahmud said a prayer of thanks to “Allah, the lord of the universe.” Utbi gives the date of this “splendid and celebrated action” as 27 November 1001.

But an even worse fate awaited Jayapala.

As an Asuravijayi, this is what Mahmud did, described again in the glowing words of Utbi.

Mahmud of Ghazni then freed Jayapala on the condition of receiving fifty elephants plus 2,00,000 dirhams till which time he had to leave his son and grandson as hostages. This is perhaps the first in an uncountable line of such hostage-taking of Hindu princes, an act which the British reciprocated with Tipu Sultan, the Tyrant of Mysore. Deceased Tipu apologists like Girish Karnad will naturally conceal this bigoted, heartless historical precedent.

Jayapaladeva’s end was truly befitting his life as an unsullied warrior of Sanatana Dharma: fearless, courageous, proud, relentless, determined, uncompromising and honourable. After his release from Mahmud’s bondage, he wrote to his son Anandapala and publicly declared to his citizens that he was unfit to rule any longer. He had let them down and he himself had been degraded by this cow-eating, Murti-breaking Mleccha. Death was preferable to a life of shame and dishonour. Towards the end of 1001 CE, this noble Kshatriya, in accordance with the code of his ancient Dharma so dear to him, to preserve which he fought continuously, shaved off his head, lay down on a pyre and set fire to it, to himself.

Concluded

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.