- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

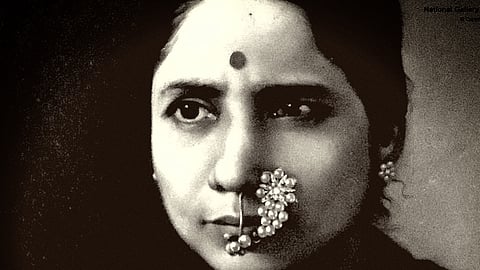

ABOUT A CENTURY AGO, a health officer named Kershaw Dinshaw Khambata at the Poona Municipality issued a strongly-worded press note. He advised Hindu women against wearing the Nath or nose-ornament because “this custom tends to keep the nose unclean and the ornament becomes a nuisance to the health of the wearer.”

A huge controversy erupted almost immediately. The Hindu community alleged that Mr. Khambata had no right to interfere in its traditional practices and customs. The Poona of that period was thickly orthodox. It prided itself in sticking to the time-honoured modes of dressing, behaviour, manners and other aspects of everyday life. The Peshwa imprint was deep enough not to be erased that easily. Definitely not by a public health official. Especially in a realm that was related to the ornamentation of their women. In their inherited cultural and social memory, the Nath signified a range of connotations including but not limited to beauty, piety, and auspiciousness. Above all, the Nath was one of the chief markers of the notion of a Hindu woman as a Sumangali.

But the Hindu community of Poona was not alone in this. The Nath held this preeminence across the Hindu community in Bharatavarsha. For close to a millennium. Hindu deities were painted and sculpted and described in literature as being adorned with the Nath. Sanskrit poets and writers called the Nath variously as nāsamauktika, nāsāgramuktāphala, nāsamaṇi, and nāsānguri. Equivalent words were coined in Indian languages as well: mūgubṭṭu, mūguti, mukkupuḍaka, mukkūti, etc. The Hindu community had taken for granted that the Nath enjoyed the same status and sanctity as that of other decorative ornaments such as the necklace, bangle, and anklet. And the Hindu community was wrong.

The Nath or nose-ornament or nose-ring is largely an Arabian import.

THE BODY OF RESEARCH TRACING THE ANTIQUITY of the Nath in India is quite extensive and runs up to roughly around 400 pages (based what I have been able to discover so far) and is divided into two opposing camps. One camp intends to prove that the Nath is a foreign import and the other, to prove just the opposite. This research corpus has been enriched by the contributions of stalwarts such as P.K. Gode, A.S. Altekar, M.R. Majumdar, K.P. Parab, N.N. Dasgupta, N.B. Roy, and Belvalkar. It includes an exhaustive wealth of primary sources comprising literary, sculptural, epigraphic, and religious evidence. Secondary sources include travelogues and contemporary histories written by foreigners. The ultimate verdict is in favour of a foreign origin of the Nath.

The first appearance of the nose-ornament in Bharatavarsha is around 1000 CE, i.e., at the end of the Classical Era. Every piece of primary evidence prior to this period does not mention it. In fact, there is no original Sanskrit word for ”nose-ornament” or “nose-ring.” Bharata Muni’s Natyasastra, which has an elaborate section on ornaments, does not mention it. Dharmasastra works composed in the Classical Era do not mention it. Panini does not mention it. The Amarakosha does not contain an entry for “nose-ornament.” Sculptural remains and paintings of the Classical Era do not show humans and Hindu deities wearing the nose-ornament. Likewise, the massive corpus of literature and poetry (Kavya) produced till the end of the Classical Era does not mention this term.

Dr. A.S. Altekar’s in-depth and brilliant research on the topic yields to us the following summary:

( 1 ) The nose-ring is a sign of Saubhagya or married bliss, yet in the Natyatastra, it is not included in the exhaustive list of ornaments of women.

( 2 ) Sanskrit poets and dramatists show no acquaintance with the ornament.

( 3 ) There is no word in the Sanskrit language to denote the ornament.

( 4 ) The words natha, nathia, nathni, natthaa, nathdhag found in Indian vernaculars are derived from the Prakrit word nattha, meaning the nose-string used for controlling an animal.

( 5 ) The nose-ring is not found in the sculptures at Udayagiri, Bhuvanesvara in Orissa, Bodhagaya, Patna in Bihar, Bharhut and Sanchi in Central India, at Mathura in U. P., at Taxila in the Punjab, at Ajanta, Ellora, Badami in the Deccan and Amaravati in the Madras Presidency, though these sculptures show a rich variety of women's ornaments.

( 6 ) It is clear that the nose-ring was unknown throughout the whole of India during the entire Hindu Period.

( 7 ) Hindu sculptures of Puri and Rajputana of the post-Muslim period begin to show the nose-ring tor the first time.

( 8 ) The nose-ring seems to have been clearly borrowed from the Mahomedans.

Like Altekar, P.K. Gode has extensively forayed into the antiquity of nose-rings over an incredible six-part series of scholarly articles. The sweep of his erudition and the depth and breadth of his evidence-finding is almost superhuman. If this was not enough, Gode convincingly rebuts every attempt to somehow prove that the Nath originated in Bharatavarsha. He not only concurs with Altekar but delivers a delicious punchline of sorts in the end as we shall see.

IN A SUPERB RESEARCH PAPER, published in 1942, Prof. R.T.S. Miller traces the antiquity of the nose-ring all the way back to the Old Testament. The Hebrew word for nose-ring is nezem, and Miller, after examining the eleven passages in which this term occurs, makes this interesting observation: “these passages do not all show a very favourable attitude to such ornaments” and that the nose-ring was a “foreign importation among the Hebrews, who might have inherited this custom from the ancestors they had in common with other Semitic people."

Imported from Egypt. Miller narrates the backstory to this. Around 1950 BCE, “an official of the name Sinuhe from Egypt fled to Southern Palestine and there settled among the Bedawins (Bedouins), who were called "plunderers" or "sand-dwellers" by the Egyptians.” Prof Miller also writes that the Bedouins have “kept the custom of using noserings to the present day."

P.K. Gode corroborates this by citing Edward William Lane’s 1835 book, Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, which gives a detailed list and description of the ornaments worn by Egyptian women of that period. Lane writes that the women of the “lower orders” in Cairo and in the rural areas of Egypt wore large nose-rings made of brass.

Over time, nose-rings acquired widespread popularity and appeal among all classes in the (later) Islamised societies of the Arabian peninsula, Iraq and Persia. The obvious outcome was a range of innovations and artistic finesse in making exquisite nose-rings. And when the plundering armies of Islam reached India, they brought nose-rings with them along with the fire and sword and an alleged holy book. As Islamic empires pushed deeper and farther within India, nose-rings too, became popular with the Hindu community as well.

FROM ONE PERSPECTIVE, the rapid adoption of the nose-ring by Hindus is quite a bizarre and unique phenomenon given the fact that Islam as a creed with a definite set of doctrines never acquired an iota of legitimacy among the Hindus till Mohandas Gandhi arrived on the scene. But it was not merely an adoption on the human plane. The Hindu community elevated the nose-ring to a divine altitude. Poetic and even devotional hymns were composed, describing Saraswati, Parvati, Lakshmi and other prominent Hindu (female) deities as wearing exquisite nose-rings. In fact, there is an entire Sanskrit poem unambiguously titled Nāsāmauktikapan̄cavimśati (Twenty-Five Verses on the Nose-Ornament) extolling the beauty of the nose-ornament of Goda-Devi.

The nose-ring also fastened itself in other realms. Artists and connoisseurs of Carnatic Classical Music will be widely familiar with the Nāsikabhūṣinī (Nose-Embellisher) ragam. Its earliest reference dates back to the 1750 musical treatise titled Saṅgrahacūḍāmaṇi compiled by Govindacharya. Likewise, a majority of sculptures and paintings from the medieval era onwards depict Hindu deities wearing the nose-ring.

Till this day, even in traditional Hindu households, the nose-ring on a woman is considered highly auspicious, leading P.K. Gode to remark on the “perfect innocence of the Hindu writers and poets regarding its foreign origin.” Indeed, the nose-ring is perhaps a unique phenomenon in Indian history that shows how thoroughly an imported, Islamic socio-cultural element has been digested by the Hindu community. Lest some indoctrinated eminence hold this as an example of Hindu-Muslim syncretism (sic), it must be said that the full credit for giving respectability and auspiciousness to the nose-ring belongs to the Hindus. In this context, it is worth quoting P.K. Gode again:

…Hindu ladies, who had practically an ornament for every part of their bodies before 1000 A.D., PICKED UP THE NOSE-ORNAMENT FROM SAVAGE TRIBES… In view of [the] evidence [gathered so far], it is reasonable to suppose that the Hindu ladies must have adopted the custom in imitation of the savages about 1000 A. D.

And then Gode delivers the punchline:

… THE CUSTOM OF BORING THE NOSE IS A SAVAGE ONE AND NEEDS TO BE ABANDONED BY HINDU LADIES. The Nath with all its jewels and rubies, should be discarded by our women-folk, though it is wrongly regarded as a sign of married bliss. ITS WEARING IS NOT SUPPORTED BY ANY TEXT ON HINDU DHARMA-SASTRA FROM THE EARLIEST TO THE LAST. But custom lends enchantment to the face, and our orthodox sisters are not inclined to leave the Nath to the savage tribes; on the contrary, they make their husbands pay a heavy cost for this ornament which has got the halo of antiquity…

We can only speculate that the Poona Municipal health officer Dinshaw Khambata had really no idea of this detailed history of the Nath. However, his recommendation to Hindu ladies to abandon the imported ornament, based on practical and medical grounds, tallied with that of P.K. Gode’s investigation-verified recommendation.

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.