- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

THE REGIMES OF SIMHANA II, KRISHNA AND RAMACHANDRA are especially distinguished for an explosion in cultural activity and development of new knowledge even in the non-religious and non-literary spheres although the distinction is not watertight.

The most noteworthy contribution to the Indian knowledge system occurred in the realm of astronomy. The output was encyclopaedic, learned and prodigious, and most of it emanated from the members of a scholarly family founded by Kavichakravarti Trivikrama, author of the Damayantikatha. His son Vidyapati Bhaskarabhatta was a protege of the acclaimed Paramara ruler Bhoja Raja. Bhaskarabhatta’s great-grandson was Kavisvara Mahesvaracharya who composed two works on astrology, Sekhara and Laghutika. Mahesvara’s son was the famous Bhaskaracharya, who wrote a number of works on mathematics and astronomy. His Lilavati, Siddhantasiromani and Karanakutuhala have stood the test of time. Bhaskaracharya’s grand-nephew Anantadeva was a protege of Simhana II. He wrote a commentary on the Brihajjataka of Varahamihira, and on the seventh chapter of the Brahmasphutasiddhanta of the seventh-century mathematician Brahmagupta.

It is the Sevuna cultural climate that gifted to the world the pioneering and genius-level work on music, Sangitaratnakara authored by Sarangradeva. This treatise is the most comprehensive and definitive synthesis of ancient and medieval musical knowledge of India. It has been an inevitable source-book for every single musicology text produced in India—both in the Carnatic and Hindustani tradition—ever since. It is also noteworthy that Sarangradeva was an accountant by profession in Singhana II’s court.

In the literary realm, although the output was impressive, it could not match the Gupta standard by any measure. Jalhana, a minister of Krishna compiled the famous Sanskrit anthology of verses, Suktimuktavali, Other works of the period include Vedantakalpataru a commentary on the Bhamati, which is in turn, a commentary upon Adi Sankaracharya’s Vedantasutrabhashya. The Marathi language and literature was carefully nurtured, and flourished under the Yadavas and the crowning Marathi work of the era is undoubtedly the Jnaneshwari.

But the most renowned Sanskrit writer of the Yadava age is, indisputably, the polymath Hemadri Pandita. His official position was that of a commander of the Yadava elephant brigade, a title that has been drowned in our historical memory under the sweet and expansive waters of his literary and Dharmic accomplishments. Till date, his prestige rests on the encyclopaedic work of Dharmasastra, the Chaturvargachintamani. Other minor works in the sub-genre of Dharmasastra include the Parjanyaprayoga and the Tristhalividhi. Hemadri’s treatises on astronomy are the Kalanirnaya and the Tithinirnaya. If this was not enough, he wrote a highly learned dissertation titled Ayurvedarasayana on the seminal work of Ayurveda, Ashtanga-Hridaya written by the sage Vagbhata. A minor work on statecraft is the little-known Dandavakyavali. Apart from the Chaturvargachintamani, Hemadri’s crown of knowledge was studded with two more jewels: one was the introduction of the Modi script in Marathi and the other was the establishment of a rather independent style of architecture eponymously named the Hemadpanti Architecture. Most of the renowned medieval temples in Maharashtra follow the Hemadpanti School. Prominent examples include the Gondeshwar Temple at Sinnar, the famous Tulja Bhavani at Osmanabad, the Markanda Mahadev, Chamorshi, Nagnath Temple, Aundh, and the Bhimashankar Temple at Khed. The contemporary socio-cultural consciousness of Maharashtra fondly remembers Hemadri Pandita as Hemadpant.

IN THE REALM OF POLITICAL ECONOMY and wealth-creation, the Sevunas scrupulously adhered to the time-honoured principles of all Hindu kingdoms: of nurturing and growing material abundance than relying merely on cash. The ubiquitous marker of this abundance was agricultural produce, which included a vast surplus of food grain. Even here, the competent and wise and innovative Hemadri Pandita introduced Bajra as a staple crop for the first time in the Sevuna territory proper. The Sevuna Empire also carried on extensive and vigorous trade, both inland and maritime. Most of the big towns in the kingdom were actually marketplaces. In some cases, the monarch himself identified some strategic districts and transformed them into lucrative trading centres where business was conducted on an epic scale. Business was carried on with neighbouring kingdoms such as the Kerala and the Tamil countries. Maritime and riverine trade routes (known generally as Jala-Marga) also constituted a substantial source of revenue for the Sevuna Empire, and tax was exempted on these routes.

All business activity in the Yadava realm was carried on—as in other Hindu Empires—by trading and merchant guilds of varying sizes, buying, selling and trading in an astonishing range of products. The guilds intersected with one another functionally, socially and culturally. It was not mandatory that a guild had to be native to the Sevuna dominions. In a broad sense, its headquarters could be located even in an enemy country but it could carry on its business unmolested as long as it followed the laws and customs and traditions of the Sevuna country.

The most powerful merchant guild was undoubtedly the Vira-Banajiga, an ancient and highly influential business community that eventually developed close trading contacts with Assyria and Babylon among others. During the Sevuna rule, it was headquartered at Aihole, its traditional home. Other guilds included the Mahajanas, Nagaras (or Nakharas), Settis, Settiguttas, Mummuridandas, Okkalus, Vadda-Vyavaharis, and so on. Specialised professional guilds such as Telligas and Gaatrigas also wielded considerable influence. Several eye-opening documents published during the reign of the Hoysala King Someshvara, a contemporary of the Sevuna ruler Singhana, reveal a profound insight into the overall climate in the era of Hindu kingdoms in Dakshinapatha. The summary of these records gives us quite an uplifting portrait of an influential Malayala merchant named Kunjanambi Setti.

An expert in testing all manner of gems, understanding in a moment the wishes of kings, filled with ability to counsel, skilled in learning, and great in generosity was Kunjanambi, the promoter of the fortunes of the Maleyala [i.e., Malayala] family. Pleasing both the Hoysala emperor in the south, and Singhana himself in the north, he formed an alliance between the two kings which was universally praised, and obtained credit in negotiating for peace and war as an embodiment of perfect truth (satyavakya) and an ornament of mercy… He at once supplied [i.e., goods, business, money, etc], and obtained extensive merit to and from the Chola and Pandya rulers. No Setti was equal to Kunjanambi throughout the Hoysala kingdom. An emperor of justice, honoured in the great Hoysala kingdom, of kind speech, a tree of abundance in natural wisdom, delighting in truth, thus did all the world unceasingly extol Kunjanambi-Setti as a collection of unnumbered good qualities.

Most guilds also maintained private armies, a practice dating back almost to the Vedic era. Apart from paying taxes, they supplied loans to the exchequer in times of emergency, financed and participated in wars, engaged in large-scale philanthropic work and contributed substantially to community-building activities such as endowing temples, sponsoring festivals, and giving patronage to the arts and culture.

The combined picture we get of the Yadava economy is this: a prosperous universe of material abundance including but not limited to a perennial supply of essential needs like food grains, vegetables, fruit, clothes, cattle, jaggery, sugar, oil, camphor, etc. The enhanced side of this prosperity was a similar abundance of valuable goods like precious metals, pearls, rubies, and priceless stones, all of which were purchased and sold freely in the bazaars of Devagiri, Aihole, Konkan and elsewhere. A good quantity of these precious items were transported via a dedicated sea-fleet, which the Sevunas had built up after their conquest of Konkan. Other modes included elephants, horses, bullocks, donkeys, and buffaloes.

There is no better tribute to the prowess, dexterity and expertise of the business guilds than Singhana’s laudatory Kannada inscription etched in their honour:

Vaiśyakulānvayaprasūtarum kraya vikrayagaḷindarthamaṁ percisi...

Born of the Vaishya-Kula [business lineage] and increasing the wealth [of the kingdom] by purchase and sale.

PERHAPS THE MOST straightforward indicator of the Sevuna economic prosperity is the glittering world of its coinage. Thankfully, some of this coinage has survived till our own time, and the first thing that stands out here is the use only of gold coins as legal tender. At least ten inscriptions unearthed from various regions of the Sevuna dominions show that gold coins were issued by the monarch and were extensively used in transactions such as the purchase and sale of land and other goods. Specialised mints were established for the purpose and several varieties of coins were issued. Silver coins too, were used to a lesser extent.

Each gold coin weighed 57.25 grams and some were named according to their denomination. The fact that most of these names exactly corresponded with the currency nomenclature and measurements in vogue since the Vedic period is the financial facet showing the unbroken and perennial stream of Hindu civilisation. Coin units such as Nishka, Suvarna, Pana, and Tanka, which were commonplace in the Yadava regime had mostly preserved their ancient usage intact. The generic name for gold coins issued by various Sevuna monarchs is the Padma-Tanka, because the image of the Padma or lotus is engraved into them. The name of the issuing king is inscribed above the lotus: Singhana, Kanhapa (or Kanhara), Mahadeva and Sri Rama.

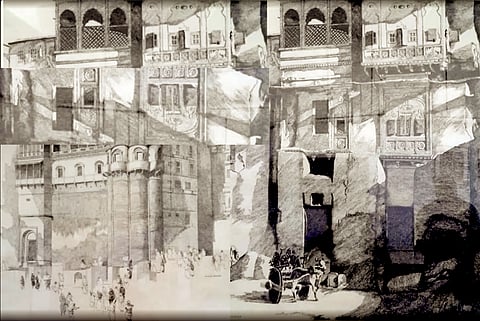

THE SEVUNA CAPITAL DEVAGIRI naturally reflected the Empire’s prosperity and its seemingly endless capacity for generating inexhaustible wealth. A close reading of the sacred work Jnanesvari gives us valuable information about the prosperity of Dakshinapatha under Yadava rule. In general, this is the portrait of Devagiri that we get after reading the primary sources narrating the history of the Sevunas. The portrait clearly epitomises its name: mountain of the Gods.

The main streets of Devagiri and other important towns and cities of the empire were lined with the shops of goldsmiths, silversmiths, and dealers in pearls and fine and costly muslins. There were many wealthy householders and there was therefore a great demand for such articles, since rich men sought eagerly for ornaments with which to adorn themselves, their wives, their children and the images of gods. Ornaments and bullion were often buried underground in the houses of the more opulent. These lived in three-storied houses, with good windows and doors, painted with pictures on the outer sides, and having guards stationed at the entrance. Cooks, umbrella-bearers and betel-carriers were among the servants who usually formed their retinues. The palanquin was the normal fashionable means of conveyance, but when a large number of people were to be transported, as in the case of a marriage party, even the rich used to travel in bullock carts.

This was truly the wealth of eons that the Sevunas had created, grown and sustained over generations through a complex, interconnected web of piety, hard work, skill, expertise, and above all, Dharma. And this was the wealth that the Turushka barbarian heartlessly plundered and reduced the beautiful Devagiri into a smoking ruin. Needless, it was the typical Islamic modus operandi of feral savagery that is incapable of building anything but has no qualms in wrecking beauty and prosperity.

The wealth of Devagiri directly funded Ala-ud-din's tyrannical Islamic sultanate.

Concluded

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.