- Commentary

- History Vignettes

- Notes on Culture

- Dispatches

- Podcasts

- Indian LanguagesIndian Languages

- Support

Years before R.C. Majumdar wrote his classic and authoritative History of the Freedom Movement in India, the legendary philosopher-litterateur-journalist D.V. Gundappa (or DVG) observed in his incisive monograph, Vruttapatrike (Newspaper) that

Before the advent of Gandhi there was an open atmosphere in public discourse… After Gandhiji took the stage, this culture of free and open disagreement and debates vanished. It was said that the political stand of the entire country should be one, and that Gandhiji’s frontal leadership should be unhindered. It was said that if Gandhiji spoke, the nation spoke. The reasoning offered was as follows: unless the nation adopted this unquestioning mentality, we would not get freedom from the British… from then onwards, People were prohibited from taking his name without the mandatory honorific of “Mahatma.” Gandhiji’s thought was the nation’s thought.

This would prove highly clairvoyant when we compare R.C. Majumdar recounting the words of Gandhi’s close confidant, Pyarelal who lamented the fact that Gandhi’s influence over the Congress top leadership had irreversibly waned away around the Quit India Movement:

Such a thing would have been inconceivable in olden days. Even when he was ranging over the length and breadth of India they [Congress leadership] did not fail to consult him before taking any vital decision.

To put this bluntly, the top Congress leadership had no use for Gandhi any longer. Unlike Gandhi, they had clearly, accurately seen the message in 1942: the British was one of the biggest casualties of World War II and England could no longer afford to retain its largest and wealthiest colony. As a climax of sorts, The Blitz had bombed and ravaged London unremittingly for nearly two months and “Great” Britain was facing extraordinary financial ruin. Neither was Subash Chandra Bose helping the matters. India would soon be free even as Gandhi was still feverishly chasing his delusion of Hindu-Muslim “equal” brotherhood.

Gandhi’s non-violent dictatorship of whimsical and emotional blackmail had reached its logical end.

R.C. Majumdar elaborates in some detail.

******

The tragedy of Gandhi’s life was that these members of his inner council, who followed him for more than twenty years, with unquestioned obedience, took the fatal steps leading to the partition of India without his knowledge, not speak of his consent…Whether Gandhi was right and his followers wrong, does not concern us here. But it certainly shows that reason ultimately took the place of blind faith and devotion to Gandhi.

We may also refer to a few other cherished ideals of Gandhi. One of them was the universal adoption of Charka or spinning wheel and Khaddar or home-spun cloth. These might be economically helpful to certain classes, but the whole thing was carried to a ridiculous excess when, failing voluntary acceptance, at Gandhi’s insistence, regular spinning was endowed with a mystic power and made an essential qualification for the membership of the Indian National Congress, and habitual wearing of Khaddar a necessary qualification for holding any office in the Congress organization. This was indeed a unique feature in a political organization, to which posterity will look back with amazement, not unmingled with…amusement, as the idiosyncrasy of a great political leader. No wonder, that in popular view the semi-religious cult of Charka shortly came to be regarded as a panacea for all evils…from which India was suffering. That myth has been exploded and the Charka is now mostly heard of only in connection with the ceremonial function on the death or birth anniversary of Gandhi. But the Charka was really a symbol of Gandhi’s undisguised contempt for, and open hostility towards, mechanized industry of all kinds…

Editorial Note: One wonders what Mahatma Gandhi would say or how he would react if he saw members of the selfsame Congress party behaving today in this fashion. Or whether he would revise his views and conception of his other great ideal: Brahmacharya or celibacy to attain which he performed extraordinary (read: perverse) “experiments.”

The same remark applies to Gandhi’s noble efforts for the uplift of the Harijans…Though the actual success attained by him may not be very great…there is no doubt that he quickened the social consciousness of the entire Hindu community…But here, again, his unduly excessive zeal for this side-issue led him to sacrifice the larger interests of the country. He also overdid the part of the friend of the poor and the untouchables by travelling in the third class in the railway and occasionally living in the Bhangi colony in Delhi, causing heavy expenditure to the Government for making his journey and residence comfortable….It would be strange…if he had not known it and regarded the amenities which he enjoyed in the third class Railway compartment and in the Bhangi colony as quite normal…

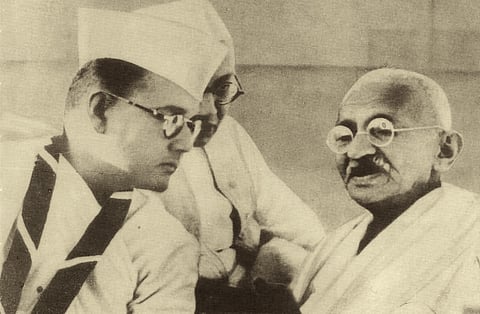

Next to Gandhi, the most dominant figure in the struggle for India’s freedom was undoubtedly Subhas Chandra Bose…His unique personality shone forth when he, alone of all the leading figures in the inner circle of the Congress, kept himself unaffected by the magic charm of Mahatma Gandhi. Hugh Toye, an English biographer of Bose, reckons…”not only…the British were wrong but that Gandhi was wrong, that the Indian struggle had no place for mystics and vague philosophers.”… The…outraged British sentiments…have not yet forgiven Bose. Their instinctive recognition of Gandhi as friend and Bose as the worst enemy would one day constitute the greatest tribute to Subhas Bose…

Gandhi’s ideal in life was the establishment of Satyagraha, and everything else was secondary; even the freedom of India had no meaning or value to him in case it involved a sacrifice of this ideal.

To be continued

The Dharma Dispatch is now available on Telegram! For original and insightful narratives on Indian Culture and History, subscribe to us on Telegram.